“A journey is a person itself; no two are alike. And all plans, safeguards, policing, and coercion are fruitless. We find after years of struggle that we do not take a trip; a trip takes us.”

—John Steinbeck, Travels with Charley: In Search of America

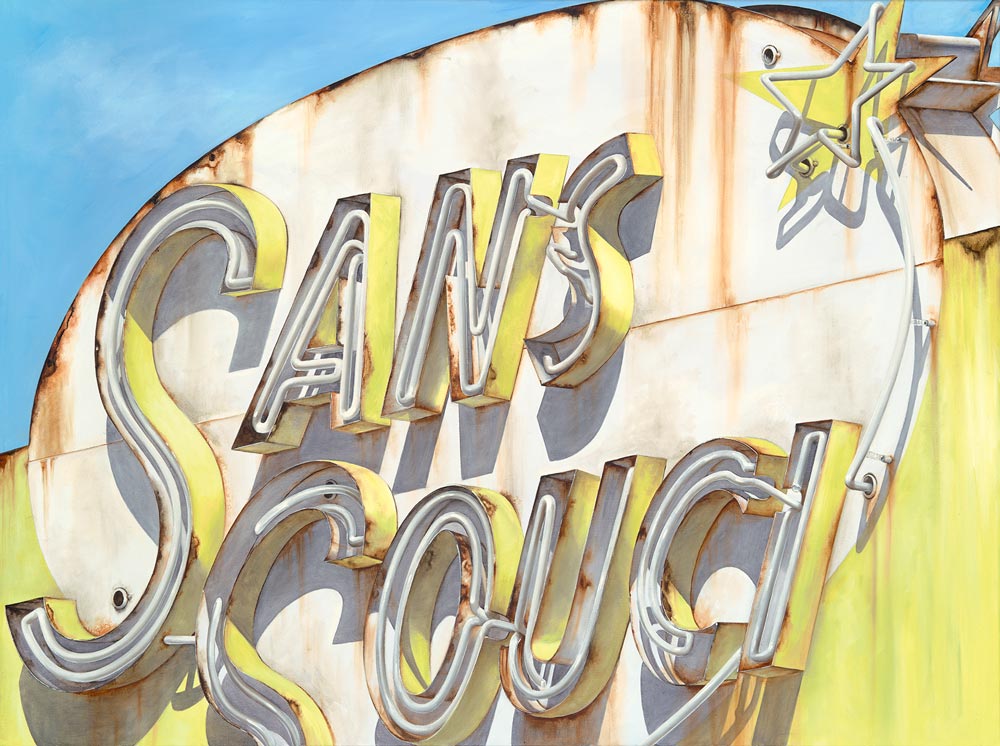

San Souci

36x48in

Oil on Canvas

2015

Seattle skies start to close at the end of October, sealing the sun away. As an oil painter, I rely on—and crave—that light. So, I take that as my cue to gather my brushes and canvases, clothes and books, husband, cat and duck, and head south to New Orleans for the winter. Usually, we fly the 3,600 miles to Louisiana, but last November we drove it in our truck, with a camper and a U-Haul. In Pendleton, OR we hit snow. At Cabbage Hill, OR—also called Deadman’s Pass—we lost the heater, but crossed the pass safely in convoy with an alpaca farmer.

Huddled under blankets in the cab with the cat, we started questioning the wisdom of this winter drive. But, then, we passed into Sedona, AZ, where the skies open so blue and wide you’d drown. We joined up with historic Route 66. And there they are: the signs.

. . .

I’m always drawn to human artifacts. Signs and typography, architecture, cemeteries, factories—places and objects that trace a trajectory of where we have been and how we’ve striven to get there. Facades, molding, wrenches, signposts: they are evidence of human perseverance and determination. I consider my paintings portraits. Like the wrinkles and blemishes you’d find on a human subject, the rust and the peeling are just signs of time and experience, not neglect. But, you’ll never see the makers of these objects in my paintings, just their shadows, the lasting contributions they’ve made.

Though I live primarily in Seattle, I rely on reference photos taken all around the country, particularly from highways and small towns. Seattle has always been the largest city in the region, but the recent influx of money and newcomers means its industrial zones—and my potential pool of subjects—are fast disappearing. In part, this is why we’re bouncing down Route 66, shivering, my camera in hand. I travel as much as possible for my research. Having boots on the ground in these places reveals the people, the economy, the history of a place. I gain insight into the industry that has grown and shrank over the life of the town. When other people take a vacation, they want to go to the beach. I want to go to Detroit, Cleveland, Fresno, Gary, Flint.

Like the wrinkles and blemishes you’d find on a human subject, the rust and the peeling are just signs of time and experience, not neglect.

Ballard Bardahl, 48x48in, Oil on Canvas, 2015

Half Moon Bar, 48x48in, Oil on Canvas, 2015

You’re not supposed to be attached to things, but I am. I have a couch in my studio from my grandparents’ house, with springs and stuffing exploding out the side. I won’t get rid of it—I won’t even reupholster it. My uncle taught me to draw a three-dimensional box on that couch. Objects have resonance, and meaning, and a solidity that can remain long after their maker has gone. I often hear from my collectors there is a sadness to what I paint, that these signs and facades are neglected and fading away. I don’t agree: most of my subjects are proudly standing exactly where they were erected decades ago. They are still doing their jobs. They’re still beckoning travelers off the highway with lights and promise of camaraderie, safety, nourishment.

. . .

We whipped past Albuquerque—frosted over, silent, skies low—and soon we re-routed due to ice. We emerged in the tiny town of Vaughn, NM (population 431), and within a yard of the city limit I was lovestruck. A neon sign for the Yucca Motel—an arrow arcing like a perfect yellow boomerang high above, a placard proudly proclaiming Color TV in technicolor hues—invited me to paint it like a French girl. I snapped a dozen photos, and we rolled on—smack into another perfect candidate. Serendipity.

Over huevos at the Ranch House Cafe, I mused. What if I lived here? Where would I buy my art supplies? Who would come visit? Would I know everyone in town? How close is the nearest airport? Would my husband run for mayor? It’s easy to fall into the trap of imagining that every person lives the same life in their city the same way we do in ours. That’s why I’m out here.

Paint

36x48in

Oil on Canvas

2014

Leaving Seattle’s mentality, rolling slowly out across the country and letting it swallow us up, it brought me into a different head-space. I crept up on New Orleans slowly, letting my senses steep in otherness, like wading into a pool. The two cities are like clothespins on a line—strong, sharp, finite—and the time and geography between them is more muted, softer, somehow more uncertain. In some ways, small towns that retained their industrial bases, or haven’t yet remodeled, are like glimpses into time. Time capsules.

I sipped diner coffee. I’m itching to get at my canvases, packed tightly into the back of the U-Haul.

. . .

F

24x24in

Oil on Canvas

2014

More than a week after we fueled up in Seattle, we reached Cajun country, and hit the brakes. The light is different here, the shadows are different, the air is different. New Orleans is my second home, and it has been for more than 16 years. Though I don’t radically change the subjects of my work while I spend the winter there, I have the light back in the sky and on my canvases. I can get dramatic skies in the summer that look like Seattle’s winter storms. Long, slow shadows are great in winter months, but here in NOLA there is sun to go along with them—and two extra hours of daylight.

When you’re up on the levee you can see the boats coming down the Mississippi. The river was extra high then, and they opened spillways to prepare for the water coming down. From outside the window, I heard the soft murmur of neighbors talking; bike bells ringing; mournful ship horns; and the metal on metal orchestra of train cars slamming into each other to link up. Mardi Gras preparations would happen soon. It was Christmas time, and 80 degrees outside.

. . .

My studio space there is temporary, precarious. My Seattle studio is organized, but in NOLA canvases are everywhere, and I try to embrace the idea of stirring up my patterns and approach. I paint by building layers with glazes, which means having lots of room and time for layers to dry. So, no matter where I am, I work on four paintings simultaneously, or I’d never finish one.

. . .

From out of a box I pull my five whites: zinc white for transparency, zinc-titanium white, titanium white, brilliant yellow extra pale for warmth and cool, blue white. I pull up a reference photo from Vaughn, and set to work.

I adjust the curtains. I’ve come 3,600 miles to find light. Here it is.

Pink Champagne, 36x48in, Oil on Canvas, 2015

Hubig’s, 16x20in, Oil on Canvas, 2014