Polaroid… oh what a household name! Chalk it up there next to Kellogg’s, Tupperware and Ovaltine—the greats of yesteryear. But, times have changed, in the last 10 years, Polaroid has gone bankrupt, been sold multiple times, and made the unfortunate declaration to discontinue its iconic film. They destroyed the machines, quit ordering essential materials, and rode the short wave out of the instant film business.

It was social photography at its apex. Images could be passed around and gifted in the moment. In the 1970s alone, photographers were shooting a billion plus images per year.

Regardless of its exit from the instant market, Polaroid is still synonymous with those square formatted “flat little bags” a good number of folks have come to love. The film was revolutionary, daylight development and quick. When the integral SX-70 film was launched, Edward Land, the founder of Polaroid, was featured on the cover of both Time and Life Magazines. Save the time and money from the photo-lab, buy Polaroid and get your images NOW! Want to get a bit voyeuristic? Make some nudes? Not a problem with self-developing film! It was social photography at its apex. Images could be passed around and gifted in the moment. In the 1970s alone, photographers were shooting a billion plus images per year.

What is so darn special about the Polaroid for me?

As our society becomes increasingly materialistic, we begin to lose the tangible photograph.

First off, with a Polaroid, there is no reproducing the original. Its objectness is singular, and its irreplicable nature is what makes it magical. They are a photographic one-off, a unique copy with a chemical process that cannot be repeated. Roland Barthes’ comment holds no water with Polaroids: “What we photograph reproduces to infinity what has occurred only once.” A Polaroid’s oneness, allows the packet film to retain its singular aura. A scanned Polaroid is not a Polaroid. Its framing, composite chemicals and past travels cannot be digitized—the medium is the message. The physical medium, its embodied physical process and objectness, became prioritized over composition or image quality. This is, in some senses, the onset of a digital paradox: As our society becomes increasingly materialistic, we begin to lose the tangible photograph. Our technological fetishism overrides our commodity fetishism. This is again what makes the Polaroid of value, a photographic process with a unique and physical outcome. Its value is further compounded by market scarcity and issues of quality, with the last batches having an expiration date of August 2009. At a cost of $3 per image, larger projects are expensive. Every photograph is taken with added hesitation, knowing each image reduces the finite stock.

I’ve found the Polaroid camera is magical in its engineering, but also can be an unpredictable monster, tending to misfire or break easy. This only increases the risk factor in shooting. I stick to a three shot maximum; if I think there is a shot really worth taking, I’ll try to get it in three exposures or less. One of my favorite images is of the dead baby deer. That final image was my third attempt, as the other two did not properly eject. Another failed exposure and I would have given up on the image. It is risky business standing on a busy highway trying to focus on road-kill, a fourth attempt would have been too much.

Using the original Polaroid stock seems naively poetic, a dying medium to document a decadent condition. Both the film and the rural lifestyle thrived in a former time and as we move forward, our connection to both begins to dissipate.

Using Polaroid film in The Last Best West

It was those who could cope with large landscapes, those who knew what to do with wide spaces, who settled the Canadian West—the dreamers, the outcasts, the durable, the duped, and the downright determined. To leave all you knew behind, reduce your possessions to a wooden box, and take only what you could carry is either very brave or very stupid. A deep mustering of the soul and a desire for something greater was what carved the Canadian West, making it unique. I wished to explore this uniqueness of a now fading ruralness with my Polaroid stock. The Polaroids address a spirit of place, the collective histories of previous people, built landscapes and events interpreted visually through my scopic regime. Using the original Polaroid stock seems naively poetic, a dying medium to document a decadent condition. Both the film and the rural lifestyle thrived in a former time and as we move forward, our connection to both begins to dissipate.

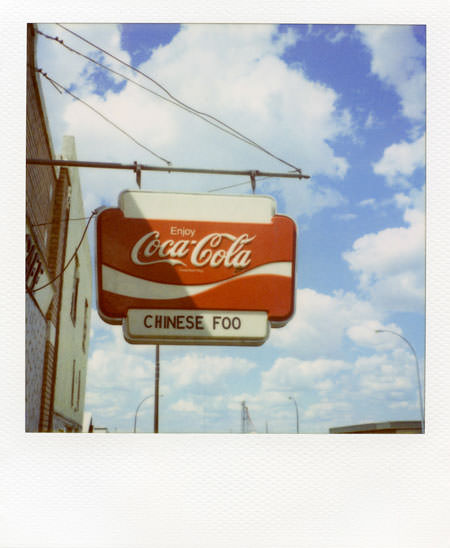

The rural Canadian West has its own cultural mannerisms, different from its southern counterpart, which it is mistakenly conflated with from time to time. Prairie towns, so recently built, lack an extended and fantastical history. As a result, they build up their recent history, and if a stirring history is lacking, they conjure one up. The result: a perplexing homage to a real and dreamed-up past made visible through oversized, monumental items. The Eiffel Tower replica in Montmartre, Saskatchewan. The world’s largest pipe in St. Claude, Manitoba, and my personal favorite, Davidson, Saskatchewan’s coffee pot. This is a trend that occurs throughout the western provinces, allowing small communities to establish questionable pitches for tourism. Some monuments like the giant T-Rex in Drumheller are quite appropriate, while others lack good imagination. Only on the prairies could a water tank be a point of interest (Harris, Saskatchewan).

Ruralites visualize their history. Towns strive to be special and stand out. They restore local fixtures embodying nostalgia to exemplify a local heritage. Town murals, restored train stations and cabooses, wooden miniatures of grain elevators and churches serve to extend the historical narrative of the town. On top of that, there is also a visual element of the urban planted in the rural—shoes on power lines, graffiti on grain bins and old barns are not uncommon. Farmers sometimes turn to fencepost and prairie art, perhaps to break up some of the monotony of straight-line driving in the west. They will nail a series of items (shoes, hats, helmets) to fence posts, anything to give a little charm.

Similar to classical swing music, or the quaint drive-in movie theater, Polaroids, like their aging American brethren, will also eventually fall by the wayside. I know in time it will happen regardless of my efforts.

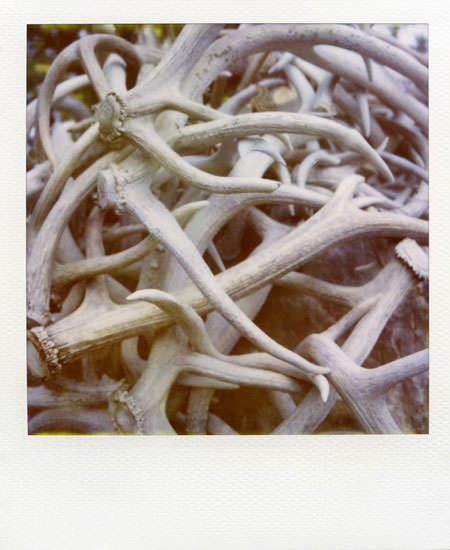

Car graveyards and expired animals are predominant in the landscape, either prized in homes or junked off the side of the road. These reject relics are left to rust, to decompose, to be eaten away by air and animals. This process, the return to the earth, is one of the most beautiful things about the west and is quietly symbolic of the current state of the area. When the death of Polaroid was announced, John Water commented that, “the world is a terrible place without Polaroid.” I am privileged to not yet know this sentiment. I know it will be a sad day when it becomes a realization for me. Similar to classical swing music, or the quaint drive-in movie theater, Polaroids, like their aging American brethren, will also eventually fall by the wayside. I know in time it will happen regardless of my efforts. My dwindling stash will either be slowly used up, or I’ll end up letting it expire on its own accord, wasting away in my fridge as I sit idly by, too scared to shoot it. I can only hope I’ll be bold enough to choose the former.