I find it very difficult to talk about art, per se. All things art seem to be a bit split down the middle these days—not that this hasn’t happened before, but it has become so very pronounced after World War II. Kudos to the term “Post Modernism” for allowing us some modicum of context with regard to discussing the whole mess.

There is never any one reason why things come about, but you can see this split everywhere. We have an economy that has arguably stagnated, a country of “haves and have nots,” and those of us who are overly educated amidst others of us with no education at all. And art reflects it. Just yesterday I heard a half-hour sequence on the radio about the opening left by the departing director of our Contemporary Art Museum in Los Angeles. It was the conclusion of the radio guest that the museum now has to choose a new director who is an “art scholar” or someone from the “hidden world of the art business.” All because of this weird split.

After School

36 x 48in

Oil on Canvas

2002

Members of the public have had to be educated to understand and appreciate much of the best art from the 20th century because art and “the masses” got divorced somewhere around 1930.

Part of the dynamic is that art now is still becoming what it is after the invention of photography and other technologies. On the one hand, unhinged from the need to depict, artists have gleefully rocketed into all kinds of risk over the last 100 years or so, trying things, and pushing boundaries. From the Impressionists and Fauvists to Duchamp, Picasso, and de Kooning, to David Park and Frank Auerbach—all the way up to folks like Tara Donovan (whose work I very much enjoy). These artists have a very deep and legitimate connection to the tradition of art. But the problem is that they have, to some degree, left pertinence behind. Members of the public have had to be educated to understand and appreciate much of the best art from the 20th century because art and “the masses” got divorced somewhere around 1930.

Failing at times to understand the art, people assess according to the hype and “experts.” Folks, sadly, cannot even tell what they enjoy anymore. They have become too insecure in even stating an opinion for fear of being ridiculed. They want to be told what is good, what to look at. There is a security in deferring to a perceived “expert.” Andy Warhol is a good example. He is much more hyped up than his contemporary, Willem de Kooning, but de Kooning is actually a much better artist.

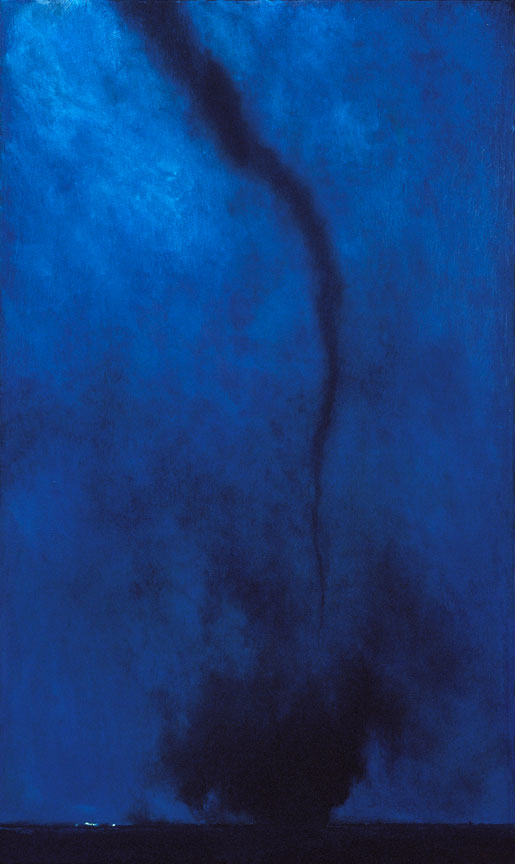

Nocturne

60 x 36in

Oil on Canvas

2006

Priorities so far askew make it very difficult to discuss art without insulating ourselves in the art community. And it works to some degree, but this is also what makes a lot of modern art arcane. On the flip side are those who would say that art of the 20th century is, at its very best, arcane. And their response is to reestablish, in their minds at least, the world of “traditional art.” This is problematic.

It is creating a world of art made with reference to art. These folks will see a Monet painting, and then not want to realize flowers and light for themselves, but want to realize Monet. Very few have the education it takes to paint like that and, even more of a problem, they do not have the time. Works painted in a world without TV required a mindset without TV. I cannot tell you how many paintings I see that have the look of classical work without the depth. All veneer and no Vermeer. And they spiral into a non-pertinence because they are trying to reject the 20th century. That is their goal.

If someone is going to paint a face as effectively as Velasquez, then it is going to come from some place other than by looking to Velasquez. Even Sargent could not do it consistently. I’ve realized this is a problem everywhere, not just with art. A great example is a hat store that I recently visited. It has, in the windows and along the shelves, all sorts of equipment like hat stretchers, blocks, irons for felting, ribbon, needles, thread—all kinds of things. But the hats are factory made and no one there knows how to use the equipment. You cannot get a hat stretched back out, or a ribbon or sweat replaced.

Folks, sadly, cannot even tell what they enjoy anymore… They want to be told what is good, what to look at.

So we end up in “traditional art” with endless imitation, because the goal, from the outset, is to be part of something else. Art being done with reference to art instead of life. Quotations of meaning past. Better than my little rant (and indeed my rant summed up into one small paragraph) is a bit of text by Edgar Payne, a very accomplished landscape painter from the early 20th century:

“If one followed altogether only that which has been done and has no new ideas, art would indeed fail and become merely a poor imitation of existing work. New thought is essential, yet, this considered alone, all truths and principles set aside, results would be equally disastrous and lead entirely to eccentricity, idiosyncrasy, and eventually to demoralization as far as true artistic quality is concerned.”

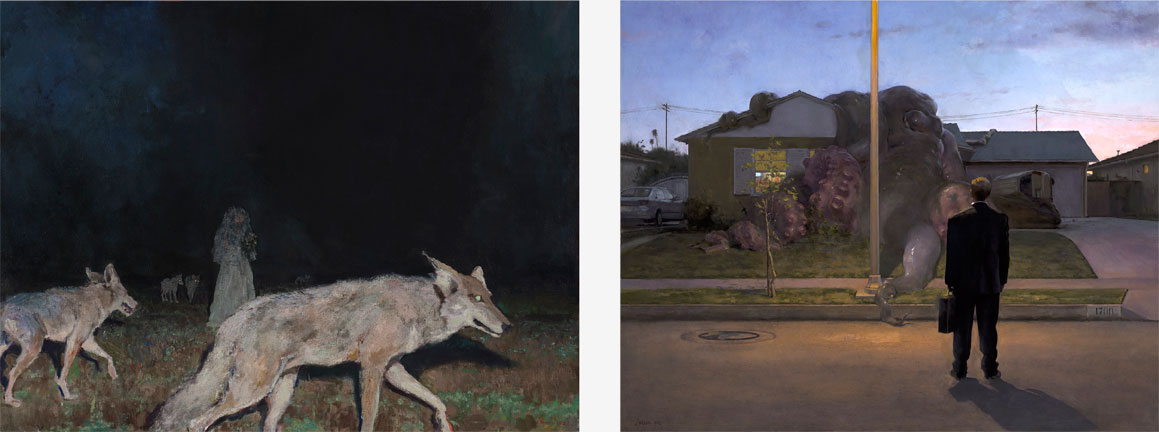

Night Hunt, 27 x 36in, Oil on Canvas, 2012

Fatigue, 48 x 60in, Oil on Canvas, 2009

Granted, this sort of thing was happening at the time of Payne’s writing, but he did not live to see it blossom into the fractured monster that it now is. The solution is to stick to the real definition of “traditional art.” And it is being done, here and there, as always, by a relatively few number of individuals. Actual traditional art, our best art and achievement on this planet, has at its summit come from an inherent need to realize. There is no contradiction to that. It does not matter if it is grapes, video projection, floating nudes, Greek gods, or colored urine. Da Vinci worked on Mona Lisa for 12 years. I’ll bet it was pretty good after 10, but it wasn’t “right” yet, for lack of a better term. And you can really see it show up when something comes along in art to codify, define, and unite disparate parts of a society.

I wish I could think of a great example right now in painting, but it’s hard. In television you have shows like Breaking Bad that draws in fans from across the board—probably one of the only times that followers of PBS’s Frontline, for instance, and followers of the Kardashian disaster can be found watching the same material.

State of the Union

41 x 66in

Oil on Canvas

2011

An interesting example in art might be the first cave painters. We know by definition that they were looking to nature and not past artists. They wanted to realize something and know it. The artists chose certain undulations and protrusions in the cave walls that best hinted at the kind of animal they wanted to depict. And even further than that, they animated some of them. Seriously. Some of the animals on the cave walls have more than one head, more than four legs. And it took a while to figure out why, but some anthropologist later connected the fact that their fire pit was positioned in the cave such that the flickering light strobed over the image and caused the overly numerous heads and limbs to move in successive selection. Courtesy of the need to realize.

One needs art education to establish sensibilities, maintain those sensibilities, and prevent a reinvention of the wheel. But the rest is a responsibility to, not an exclusion from, what is going on. Here is a great bit of text by Robert Hughes with regard to a current day painter I mentioned above, Frank Auerbach:

“Auerbach’s work suggests a way…out of the morass of ambivalence and coarsened self-reflexiveness in which so much of the art of the last twenty years has foundered. It reminds us that painting may still connect us to the whole body of the world, being more than just a conduit for debate about novelty, cultural signs and stylistic relations…. What counts most in Auerbach’s work is the sense it projects of the immediacy of experience—not through the facile rush of most neo-expressionist paintings, but in a way that is deeply meditated, impacted with cultural memories and desires which do not condescend to the secondhand discourse of quotation…. Auerbach’s struggle [is] not to ‘express himself,’ but to stabilize and define the terms of his relations to the real, resistant and experienced world: which is what art must do, today as yesterday, if it is to be more than chatter.”

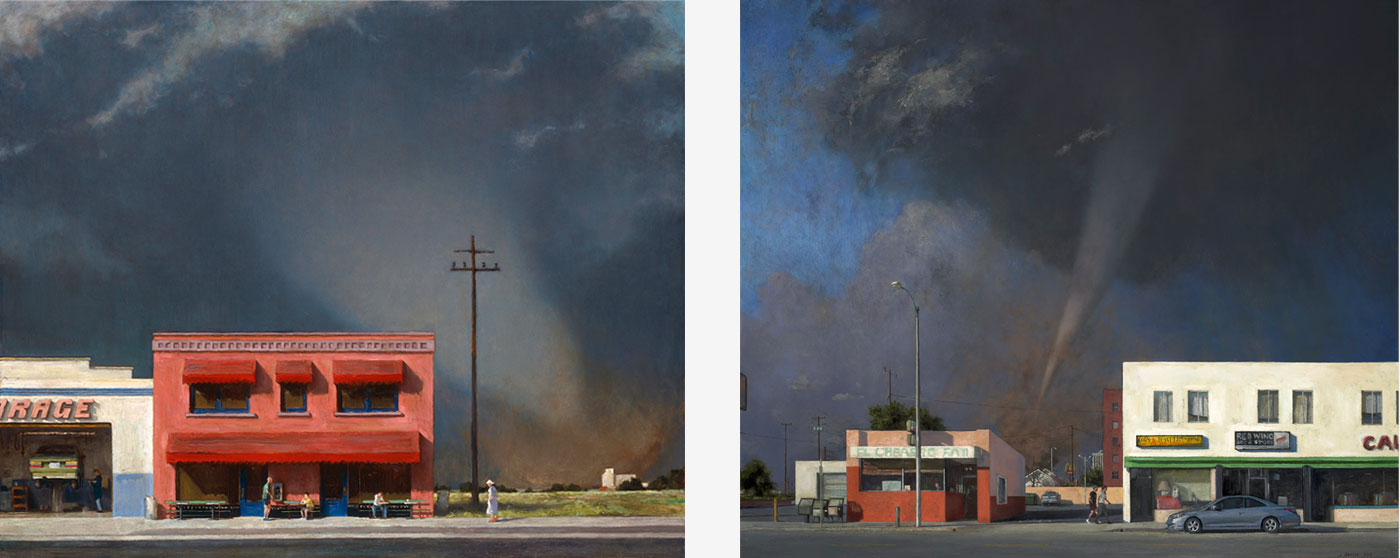

Edge of Town 3, 45 x 55in, Oil on Canvas, 2002

Edge of Town 10, 40 x 46in, Oil on Canvas, 2010

Growing up, I used to be very drawn in by the glass-encased set-ups at the Natural History Museum where other worldly animals and accountings of human endeavor sat manageable for me in some miniature form.

As far as my own work is concerned, I have become very reassured of late by folks who no longer question some of my dioramas. And I very much see my paintings as dioramas. Growing up, I used to be very drawn in by the glass-encased set-ups at the Natural History Museum where other worldly animals and accountings of human endeavor sat manageable for me in some miniature form. Some of these displays even had changing daylight effects and all sorts of neat stuff.

But the great thing is that there was an unspoken element of proposal. Those dioramas, in being contained and sectioned off from everything else, were displaying the ways in which various chosen elements fit together. The viewer had to reconcile the elements into some kind of interaction and I very much employ the memory of this experience in my work. In the same way, I feel as if I am proposing a kind of arrangement to my viewer. And it used to be that folks would look at one of my tornado paintings, for instance, and really wonder why all of the people in the foreground seemed unconcerned about the imminent danger. It was difficult for them to reconcile the arrangement. I hear that less so these days. Folks are more often reacting with a kind of “yup, I’m starting to see it now” attitude and that is making me feel a little more understood with regard to where I’m coming from. The imagery is a bit fanciful, if not comical, but it always comes from a place that is a bit more dreadful than I let on.

Scouring

48 x 60in

Oil on Canvas

2004