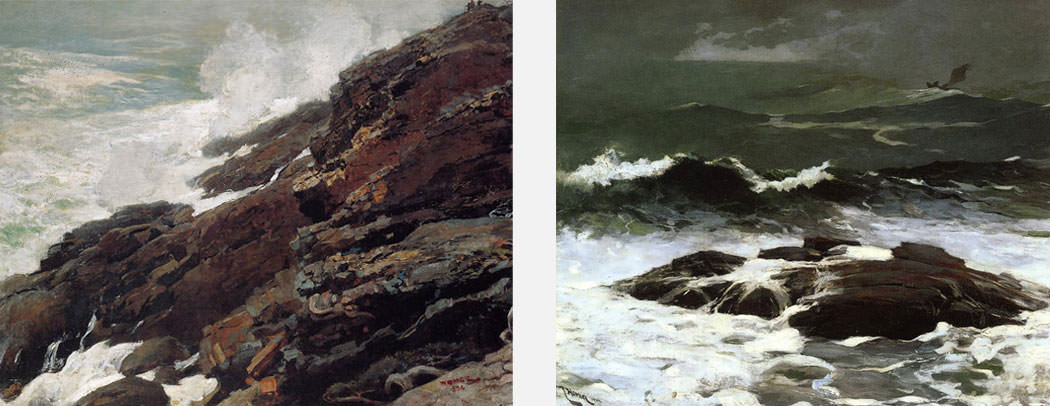

Jeremy Miranda, Oregon Ladder.

I was making a living, but not making what I really wanted to make.

During art school, and for some time after, I paid my bills painting New England seascapes. I had a few solo shows at a local gallery, developed a small, but tight following, and demand began to grow for my work. Being right out of art school, and making a living as a painter, I was tremendously grateful for the patronage (and still am). But the more time that passed, and the more seascapes I painted, a reality started to come into focus: I was making a living, but not making what I really wanted to make.

I moved to the west coast soon after, abandoned seascapes and started making my “real work,” harboring a resentment for every wave and rock that had wasted my time. Years later, after a dozen artistic directional shifts and a move back to New England, I found myself working out of a cold and lonely studio in Gloucester, Massachusetts (there are no other kind of studios come to find out). As a result of the changes, shifts, and dead ends, I was left directionless. At some point I learned that Winslow Homer had painted for years holed up in the light house down the road from my studio. As I kicked around that winter, scribbling down ideas for another “new direction” I became more interested in the similarities of our “holed up in Gloucester” personal narratives. I began to feel like I had a companion of sorts, even though 100 years or more separated us.

Winslow Homer, High Cliff, Coast of Maine.

Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC.

Winslow Homer, Summer Squall.

Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, Williamstown, MA.

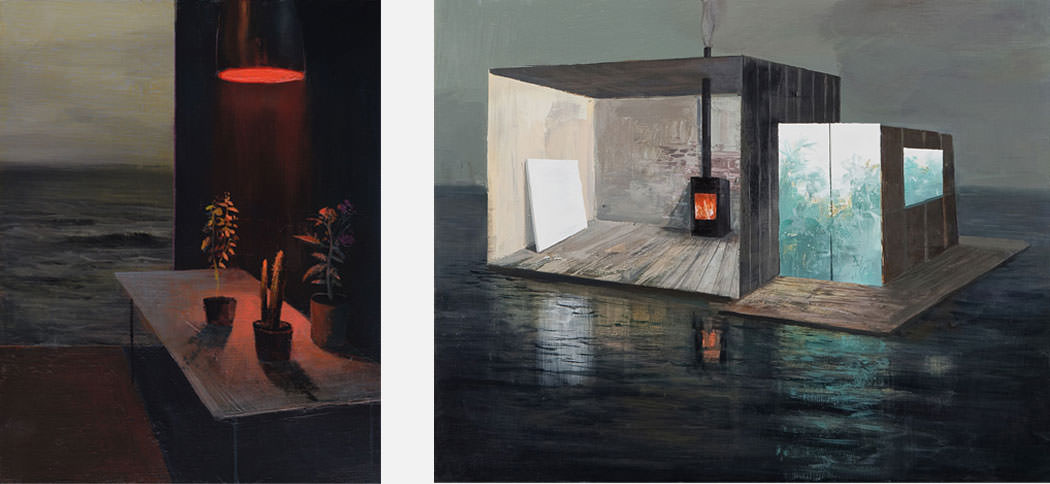

Jeremy Miranda, Dead of Winter.

Jeremy Miranda, Houseboat.

One day, while rummaging through a used bookstore for answers, I stumbled on a thick Winslow Homer monogram. I thought I knew his work well but as I flipped through the massive book I began to notice a constant evolution and shift in the tone. His work began to seem unfamiliar. The pleasant summer shores became more temperamental and foreboding, the skies darker and more obscure, and the figures, once adorned with parasols and picnic baskets now struggled in a futile battle against an uncompromising and turbulent ocean. By the end of the book, the clichés, the figures, the horizons and even so much of the color had been stripped away and you were left with a body of work that spoke about inner turmoil and a personal search for answers.

That’s when I realized where I had gone wrong. The problem was never the subject; it was my treatment, my mishandling. Homer showed me that making meaningful work is a process of stripping away what is trivial until you find what is personal in a subject.

Jeremy Miranda, Palace.