I

It’s common for artists to introduce their projects by describing how they began. I begin by describing how mine ended.

As September 2013 came to a close, talk of a U.S. government shutdown had been dominating the news for weeks, and it was a foregone conclusion that the shutdown would happen. Against this background, I ventured to the east end of the United States Capitol on the evening of Sept. 30. Not much was happening. Some media crews milled about in the grassy area east of the capitol. People left work. Armed guards stood at their stations.

Eventually, as darkness fell, I made my way over to the entrance of the house wing as groups of people began to walk up the steps. Politicans. Some of them walked in clumps. Paul Ryan walked alone, listening to music on his iPod. I waited until the representatives emerged from the wing and made the above picture. The following morning marked the beginning of the shutdown.

Since early 2011, and long before I could articulate my intent, I had been making a body of work about the broken trust between American citizens and major institutions that serve and represent the citizenry. The title National Trust is a play on words. Usually this phrase refers to historical preservation, but in this context trust means trust: something that is not tangible but felt, and ultimately can’t be photographed.

Members Only, 2013

…the government of the most powerful country in the world had shut down… [and] it felt more like a pathetic, tragicomic farce than a stone cold reality.

Sept. 30, 2013, was one of the last times I photographed for this project, and in chronological terms, Members Only, 2013 is the last picture from the final edit. Normally the exact end date of a project would be inconsequential, but the eve of the shutdown made it important to me. Over the course of the project, I had many conversations that centered around the lack of trust in American society, and here was the ultimate manifestation of why that is so. After our elected officials couldn’t reach an agreement that would have kept the government functioning, with blatant partisan rancor guiding the course of action, the government of the most powerful country in the world had shut down. For someone who wasn’t immediately affected, it felt more like a pathetic, tragicomic farce than a stone cold reality.

What else was there to say with my work? Instead of getting ready to sink my teeth into a picture-making frenzy that I could have carried out during the impending shutdown, I felt like I could let go. After a few unsuccessful attempts to get more pictures for the project, I came to accept that my work would function better as a story of spectacles, vain appearances, and calculated gestures that predated the shutdown, rather than a combination of the buildup and the blowup. Any more time spent tracking down politicians standing at lecterns or protesters congregating around institutional architecture would have just been exercises in repetition. And that is how it ended.

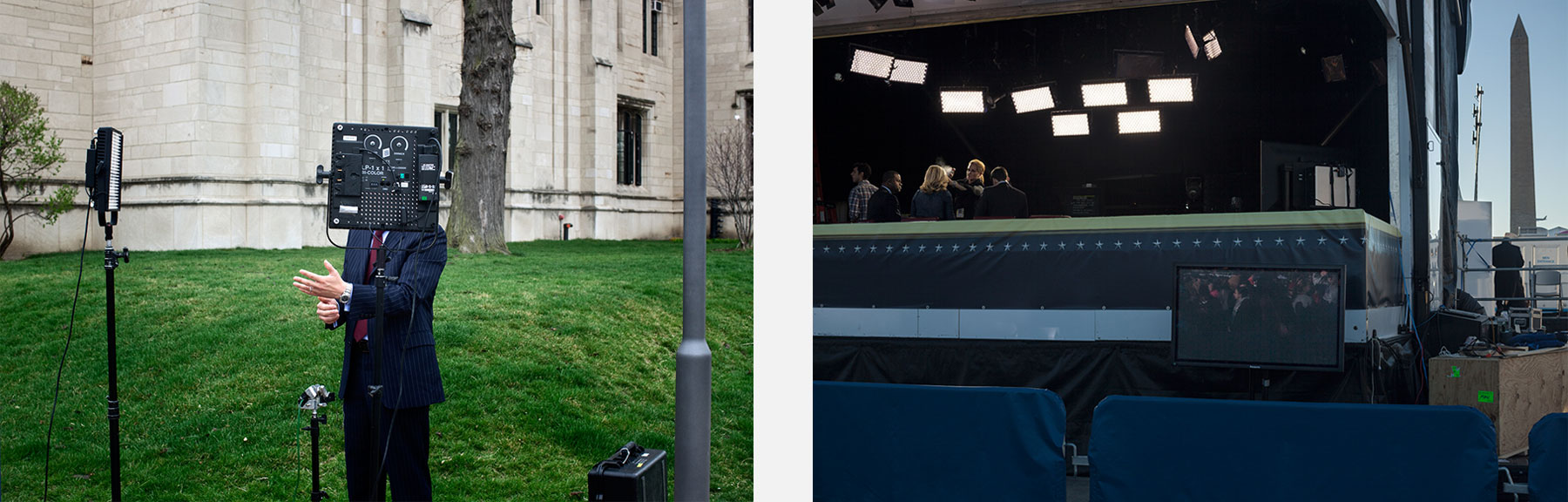

Reporter 1, 2012

National Mall, 2013

II

The subjects of National Trust range from historical structures to political spectacles and media culture, but they are all inextricably tied to appearances. Architectural forms recall the grandeur of Greco-Roman temples, and political rallies exist as meticulously staged theatre sets full of patriotic glitz. These carefully constructed façades can stand for different things, but in a sense they are intended to inspire trust among the citizenry. This trust has been shattered. Skepticism in governance is nothing new, but if public opinion polls matter, the recent level of distrust is remarkable. Trusting and believing those in power, and trusting in the appearances they create, seems like an increasingly difficult act of faith for citizens.

A lack of truth can result in a lack of trust; we have seen this happen with photography. Numerous discussions surrounding the relationship between truth and photography have flooded photographic discourse in recent years, and it has long been established that this relationship is fraught with complications. Furthermore, we live in a time in which more people participate in visual culture than ever, and anyone with even a cursory awareness of this culture knows that photography can be skewed and manipulated for various ends.

Yet, in spite of all this knowledge, we still believe. In an essay about the artist Joan Fontcuberta, Geoffrey Batchen writes that Fontcuberta’s photographic installations explore “how a medium that is indisputably fake ‘from start to finish’ can nevertheless acquire a seductive truthiness in the eyes of its viewers. In particular, Fontcuberta’s work exposes the degree to which the truths we find in photographs are dependent on faith, a mode of belief that transcends both truth and falsehood.” Batchen is pointing to the stubborn persistence of belief in photographs, even in the face of skepticism.1

Wall Street I

Batchen cites the mimetic quality, the realistic appearance of photographs as an important factor that supports this belief. But he goes on to write about a larger issue at stake. Because photographs live on after the death of the subjects they depict, “we submit ourselves to photography to deny the possibility of death, to stop time in its tracks and us with it… We are asked to adopt a belief in the capacities of photography that chooses to overlook its various artifices in the interests of securing for ourselves a life everlasting.” In other words, we are willing to suspend our disbelief in service of a grand promise, or perhaps the grandest promise of all: eternal life.2

The situation that Batchen describes – the willingness to believe in photographs even when there is knowledge of falsehood – seems to relate to the façades in my work. Those in power who use these façades, either lie, mislead, or leave the American public in the dark about critical issues such as the justifications for war in Iraq and the extent of the NSA surveillance programs, just to name a couple major incidents from the last decade and a half. It feels that truth and trust are either exhausted or scarce, at best.

But that hasn’t stopped citizens from believing. As disillusioned as American society has become, many of us still elect officials from the two major political parties, attend political rallies and events, and soak up the mainstream media. Perhaps it is too painful or inconvenient to accept that these engineered appearances are contrived façades that mask darker realities. Ultimately, it is easier for us to hope that those in power will act in our best interests, and it is easier to believe in the promises of security, liberty, and transparency. Just as we choose to believe in photographs in spite of their fiction, we choose to find truth in these façades, even when it may not exist.

Just as we choose

to believe in photographs in spite of their fiction, we choose to find truth in these façades, even when it may not exist.

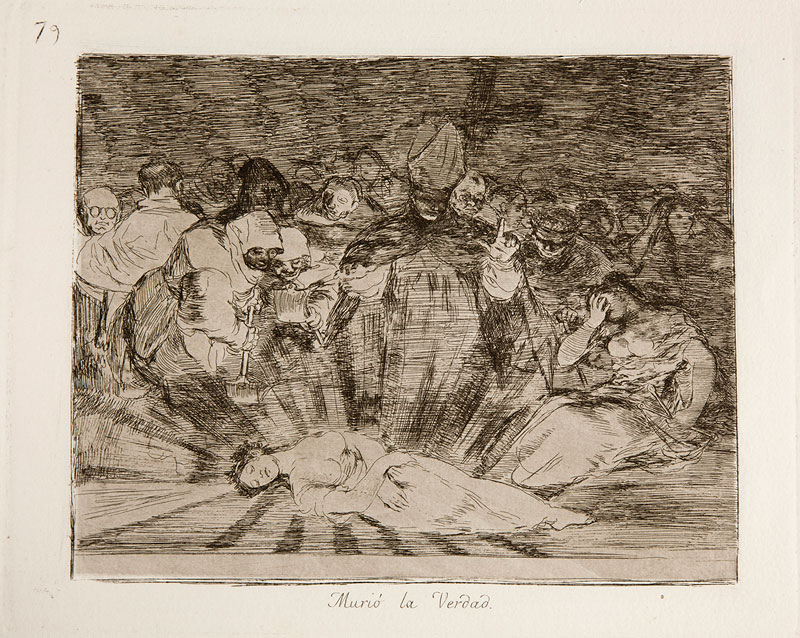

Murio la Verdad

Francisco de Goya

1814-15

Museo del Prado

III

I’m reminded of Francisco de Goya’s etching Murió la Verdad (Truth Has Died) from the Disasters of War series, a set of prints that Goya made in response to Spain’s war against Napoleon’s army at the beginning of the 19th century. In this print, Goya depicts the personification of truth as dead on the ground before a crowd of anguished people. Significantly, many of the people in the crowd are affiliated with the church, including two monks who are there to bury the body. José Manuel Matilla Rodríguez, the head of the prints and drawings department at Museo del Prado in Madrid, has written that Goya is critical of the church in this scene, pointing to the heavy involvement of clerics at the burial.3

Granted, Goya was responding to a different set of circumstances in a different age, but his assessment of truth still resonates. Furthermore, the church is yet another example of an authoritative institution in which people believe, but it has abused its power. Made exactly 200 years ago, Goya’s print reminds us that skepticism in authority is never out of the question, and that art can be a powerful force for commenting on truth, or lack thereof, in society. My work comments on a grand breach of trust in 21st century America, and now is as critical a time as ever to question where we decide to place our trust, and to question what we believe. That is my belief.

Step Stool, 2012

Supreme Court, 2013

1 Batchen, Geoffrey. “Human Nature: Joan Fontcuberta and the Truthiness of the Photograph.” Fontcuberta, Joan. The Photography of Nature & The Nature of Photography. London: MACK, 2013. 2627

2 Ibid, 27.

3 Matilla, J.M. “Desastre 79. Murió la Verdad / Desastre 80. Si resucitará?”, en Goya en tiempos de guerra,Madrid: Museo del Prado, 2008, p. 348, n. 118119. as quoted in “Goya en El Prado: Murió la Verdad.” Goya en El Prado. Museo del Prado, n.d. Web. 29 July 2014.