Though he doesn’t consider himself a creator, Seattle artist Shaun Kardinal still pulls the common thread that unites us all. Just relinquish control and give yourself over to his mesmerizing embroidery and join him in his quest to make one from many.

You wear a lot of hats. You’re an artist, photographer, videographer, sculptor and even a musician. What dynamic exists between these interests?

Having worked with many genres and media in my art practices, I do sometimes wonder where the connection lies in the oeuvre. Sometimes the work is simply an embrace of the materials, while other times it feels crucial that an idea be expressed in a particular format that I’ve not yet tried. Each honed practice adds to an arsenal for the next idea.

You’ve been experimenting with the exhibition format as a medium, can you expand on that?

Art exhibitions can be so stale. I feel this comes from a lack of cohesive connection in the experience. Must the show be a month long? What changes if it is one night? Must it live on walls or pedestals? If it is digital, to what end? What do the site specific parameters of any exhibition mean for the ideas in the work itself?

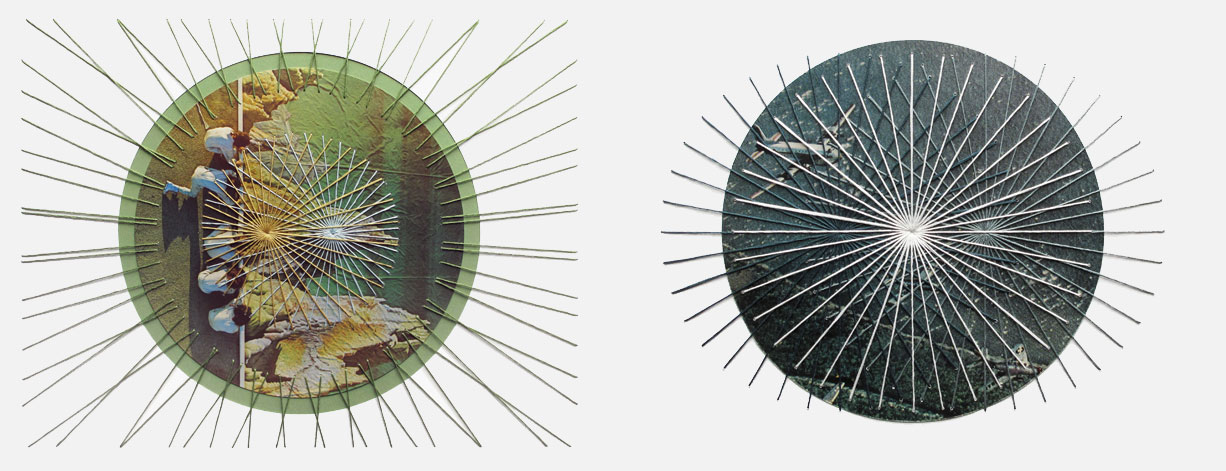

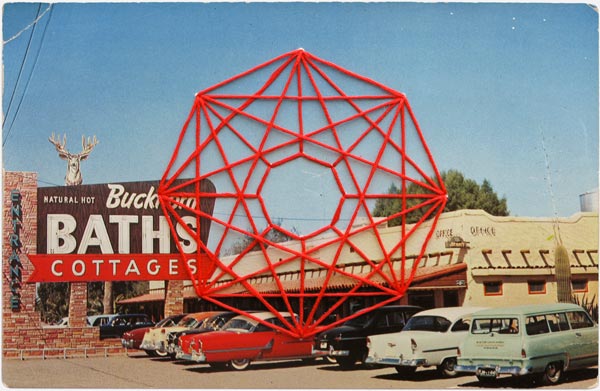

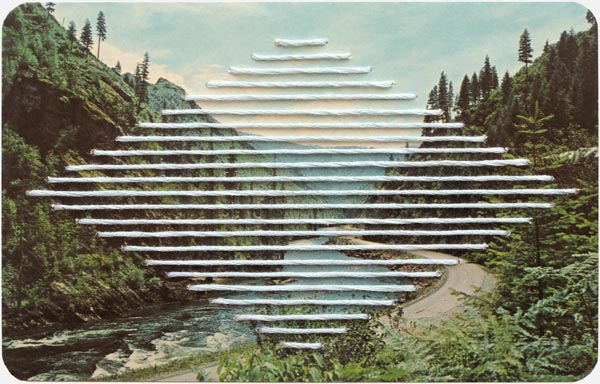

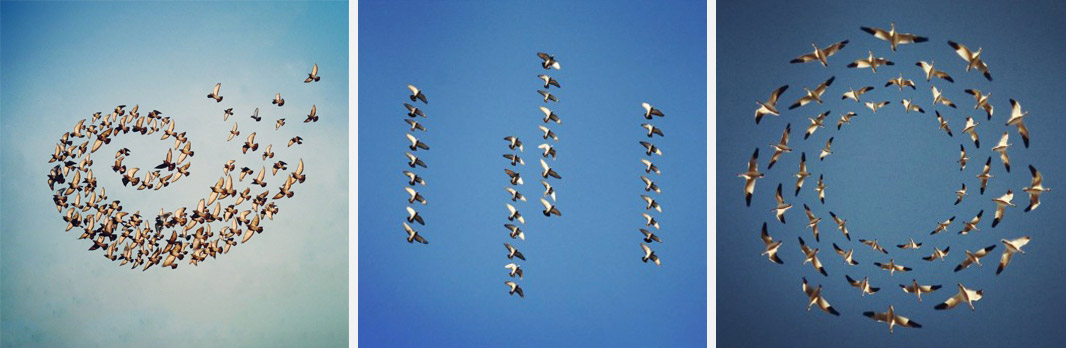

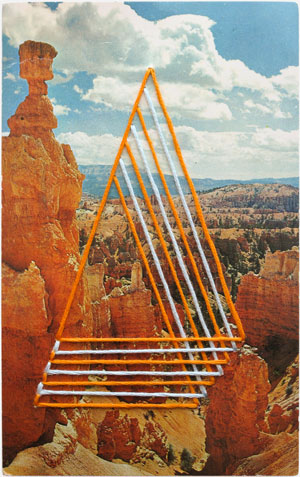

I embroidered something like 200 postcards in about two years. Those little pieces were often made as parts of one large installation, and made for sale in parts. When I moved on from that kind of work, I began thinking about those one-from-many installations, and considered how else I could push that idea forward. For a time, this became primarily digital: I posted a digital collage series on my Instagram as a one-night exhibition/pseudo performance, directed a group show on a Facebook event page, and produced an interactive physical-digital exhibition displayed on visitors’ phones. This year, the work returned to a more tangible role.

Can you tell us about your TURN project?

TURN is a year-long collaborative exhibition platform, where 12 artists take turns transforming a single piece. I kicked it off by creating a new piece for the inaugural series, and after a one-night show, handed it off to another artist. Each month, a new artist takes the piece from the last, revising and altering it for their own one-night show. It is an experiment in collaboration, and in giving up control. It is a group show with one piece.

The work has become wildly different each month, and while each artist has brought something along the lines of what I had suspected they might, each has also surprised me. Jeffry Mitchell’s TURN held last December marked the halfway point for this first iteration of the project.

I’m playing with materials for what feels like the first time. When I show people what I’m making, I can’t help but mention that “I don’t even know what it is.”

Are you satisfied creatively?

Occasionally. TURN has been an unexpectedly and remarkably affecting project for me personally—from conception to launch to its very ongoing, durational nature, it has led to many questions (and truthfully, more than one anxiety attack) about the state of my own practice and, really, my life in general. Creating a platform, I found myself asking a lot of questions—Who gets to use it? What exactly am I looking to highlight? Who am I to even be making these decisions?

Moreover, and despite it being inherent in the nature of the project as I proposed it, giving up control of what was briefly my piece was surprisingly hard at first. This has grown a little easier each month, as the excitement of the changes and the real unknown factor kicked in.

Similarly, my studio practice is in a state wholly unfamiliar to me. I’m playing with materials for what feels like the first time. When I show people what I’m making, I can’t help but mention that “I don’t even know what it is.” It’s a befuddling place for me to linger in, but for that I am ultimately thankful.

Learning to find comfort and satisfaction in these passages of time, in the journey itself, has been rewarding.

What kind of self-critiquing do you do with all of these endeavors?

Speaking of journeys, in my artistic past, I’ve tended to be a destination man. With a clear vision of what a piece will be, I generate the path that gets me to it. I tend to setup parameters for myself, restraints to work within. With embroidery, for instance, I made a conscious effort to never duplicate a pattern exactly, and to not edit the work for exhibition—if I made it, I showed it. Critique in these parameters often came after completing the piece—the destination—deciding whether or not the idea worked, and whether or not I continue working within the same parameters.

We were happy to hear you say you’re not as much of a creator as you are an “alterer.” Can you tell us more about that idea?

This idea became very relevant to me after I stopped trying to “make photographs” and embraced the use of found materials.

I like to think about how there is the same amount of rock on the earth as there has always been—constantly getting broken down into smaller pieces, and in other places, rejoined by heat, reconfigured by machine, altered by man. By this measure, I’ve never created a thing in my life.

You’ve also stated that a lot of your work is void of meaning, and you make decisions purely on aesthetics. Why is that, and what do you get out of that type of work?

Yeah, the embroidery work really was largely about honing a practice. Though I was passionate about working with the materials, the decisions made with them were usually arbitrary and instinctual. With little exception, they were not made to invoke any sort of experience, emotion or narrative—I simply enjoyed making them, wanted to be better at it, and choosing to only make aesthetic decisions fostered the rapid production. Having so many people enjoy them is a wonderful bonus for me.

Was it a cathartic process to make so many of your postcards?

I recall an intense run of exhibitions in the summer of 2013, which ended in a stretch where I embroidered 66 postcards in just a few weeks. The act of making them had usually felt meditative, but that level of output was grueling! (And turned out to be the last time I’d set my needle to paper.)

Seeing them all come together in a single installation was extremely satisfying however. And being removed from them by a few years now, it is a little flabbergasting even to me to see all those postcards!

Why did you choose the vintage postcards and ephemera for your work? What drew you to that style?

I loved the tactility of the puncture. I was attracted to the vibrant hues and romantic nostalgia that wasn’t my own. It was also fun to seek out the postcards, with their antique store ubiquity.

Your work is incredibly organized and geometric. Are those personal qualities as well?

Yes. I usually have one pile of unfinished business somewhere, but I tend to clean up as I work, organize piles. There are no icons on my desktop.

Where are some unconventional areas you look to for inspiration?

Inward, primarily. During those highly generative years of embroidery, I spent a lot of time on tumblr, with my feelers out for interesting line work and color, but I’ve never been one to look for inspiration. I think true inspiration comes without expectation.

What is the experience like of making work with the intention of giving it away for free?

Absolutely freeing. I want every visitor to my exhibitions to feel as though they’ve received or experienced something new, and through that, the piece should offer a different kind of transaction.

With Left to Your Own Devices, the exhibition displayed entirely on visitors’ phones, the cost of the exhibition experience, of receiving the work, was to give up that device for a while. The show could not have existed without that transaction, and it was more satisfying, for me, than any monetary sale.

Very simply, I enjoy the ideation and execution of my projects more than making money, and as long as I’m in a position to be able to make that happen, I would like to continue doing so.

Very simply, I enjoy the ideation and execution of my projects more than making money, and as long as I’m in a position to be able to make that happen, I would like to continue doing so.

How do you spend your down time and how important is the balance between work and life?

Netflix. Too. Many. Shows.

As for that balance, I’m not sure I’m the best person to ask for advice! I generally take on too much and still feel like it’s not enough. That, too, is a work in progress.

Being an artist, how do you like living in Seattle?

For 15 years now, Seattle has provided me with nothing but better opportunity after the last. It is an often vibrant young city experiencing major growing pains in a lot of arenas, but as an artist who has worked in many facets of the community for a decade, I can say it is getting a foothold, and I have high hopes for its future.

What is your favorite or most fulfilling project or series to date?

TURN is proving to be the most challenging and rewarding project I’ve ever taken on. However, two exhibitions immediately strike me as most fulfilling in their completion—Left to Your Own Devices and the 80-piece Alterations series I made for Bumbershoot. Both were made from many small parts to reveal a single whole.

Where do you see your work going?

I’m working with some ideas for further phone-based installations, and have a few other curatorial interests on the back burner. On the whole, I suspect I’ll continue to play with these ideas a while: one from many, parameters of execution, giving up control, exhibition format riffing, and probably a few LOLs.