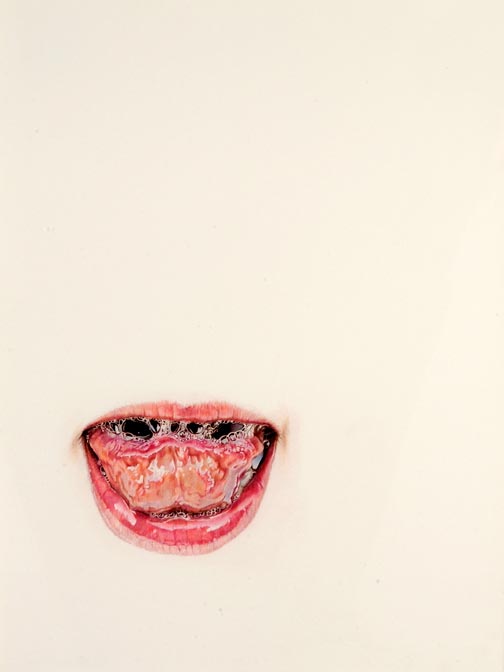

Lick Line #26

Colored Pencil on Paper

12″ x 16″

2004

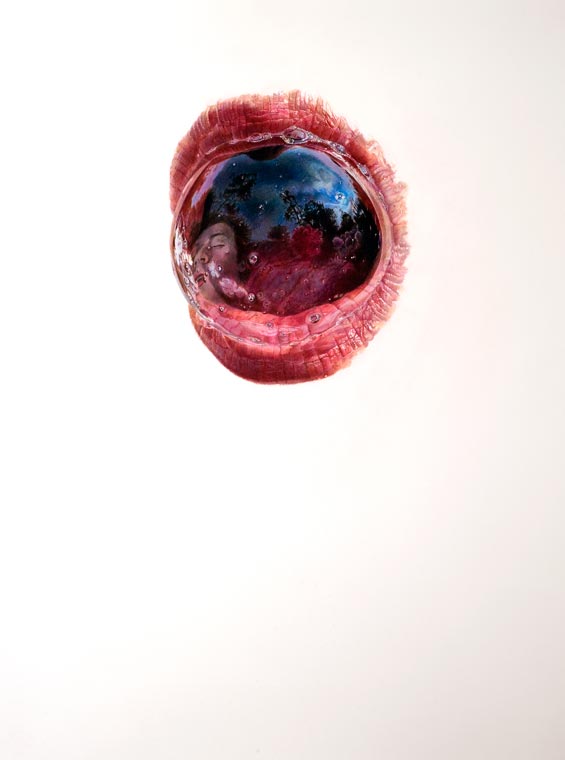

Bubblehead

Colored Pencil on Paper

18″ x 24″

2010

In addition to my studio practice, I teach drawing at a small, liberal arts university in the Northeast. I genuinely love teaching – my students are interesting, kind, committed, and willing to work their butts off. For me, teaching is the perfect social activity to balance my solitary life, drawing in the studio.

I teach drawing at all levels; in my Drawing 1 course, my students work hard to improve their skills and “look-and-put” abilities (drawing accurately, from observation). As they advance to the Studio Art major, many of my students tend to freak out, as they begin the lifelong search for ideas, fascinations, forms, or methods that are personal, and uniquely their own. It starts scarily dawning on them that skill, while seductive, is not quite “enough.”

One major struggle is how to “teach” students to find their own content – or, to use a phrase that I despise, to “be creative.” I usually speak very candidly about this never-ending struggle that I find the most challenging part of being an artist. As proof, I bring my “failure folder” to class. This is a portfolio of drawings that are technically very good; the insects, animals and other textures I drew for many, many months are persuasive and beautiful. However, there is no internal logic in these drawings. They seem random, as if you could add or subtract elements in the compositions, with no consequence or change.

One major struggle is how to “teach” students to find their own content – or, to use a phrase that I despise, to “be creative.” I usually speak very candidly about this never-ending struggle that I find the most challenging part of being an artist.

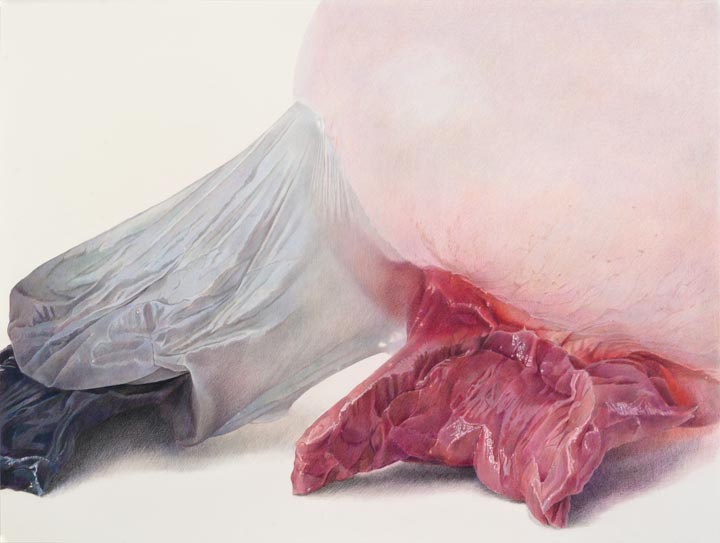

Watermelon

Colored Pencil on Paper

18″ x 24″

2012

My students are usually impressed by the meticulousness and detail in my drawings, as they are actively trying to improve their own skills. They can relate to the determination and labor required to make my hyper-realist drawings. But after the wow-factor subsides, it is apparent to everyone that no overarching content unites all the wonderfully drawn moments in these works. This is one of the launching points of recurring conversations with my students about how we find ideas, what that process is like, and what matters to each of them individually, enough to turn into art.

As they start making their “own” work, I ask students to identify their default settings, or the manner of working to which they are already comfortably predisposed. When these default settings prevent them from taking chances, I urge them to make what I call private, failure art: projects that they know will fail, but allow them to work specifically with new methods, materials, images, etc.

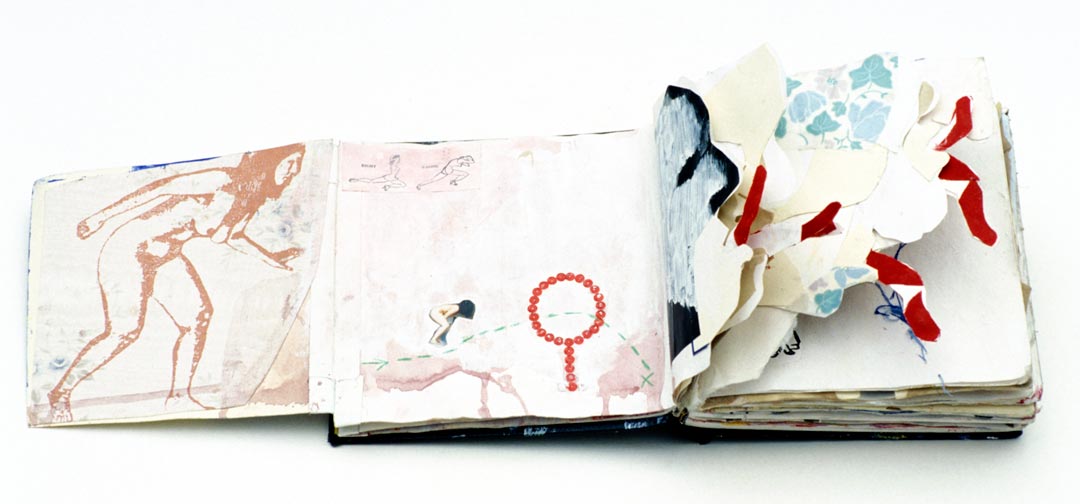

It is really hard to shake off the fear of public failure! For me, sketchbooks are essential, if nothing else but a private space for experimenting.

Sketchbook activity has been important to me for a long time, and has become the most useful way of generating content for my “finished” work. This private form gives me a place to work rapidly and unselfconsciously, and provides a place to put all my overly literal, mediocre visual ideas down, and out of my brain. The image of the mouth and tongue, which features prominently in my recent drawings, was born out of small sketchbook collages, made from a variety of materials.

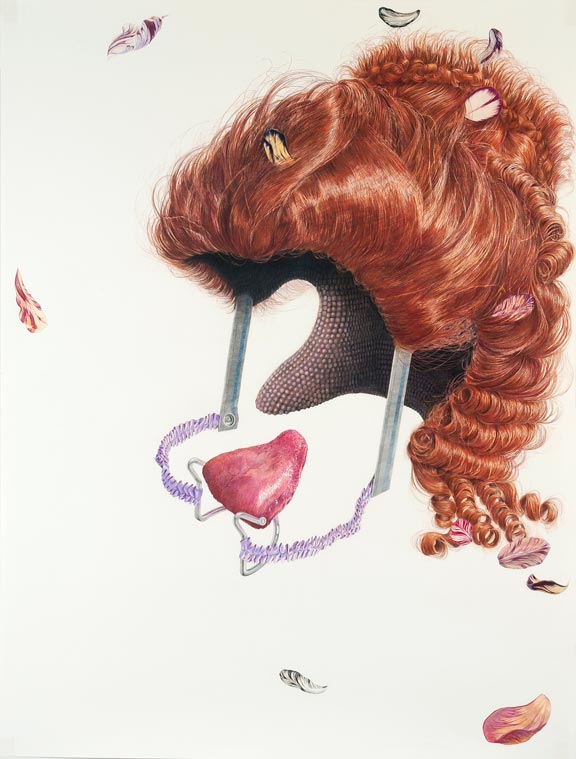

Additionally, the activities I take for granted also wind up being a pool of inspiration and ideas. I doodle whenever I am on the phone, usually sketches of objects that are half-machine parts, half body parts, and look quasi-utilitarian. One day my husband saw the pad by the phone (which back then had a cord!), and suggested I commit to really drawing one of these contraptions.

My next drawing, Wheel Of Fortune, was a large drawing of a self-gratification contraption, which featured a wheel with tongues around the perimeter. There were handles to pull to make the wheel rotate. The tongues were drawn in pastel from imagination, and looked too stylized, not real enough to get the erotic/surrealistic effect I wanted. I changed mediums to colored pencil, which allowed me to tighten up considerably, get much more detail and more accuracy in my marks. Changing to colored pencil also enabled me to see differently – it marked the start of me working hyper-realistically. In the end, the Wheel didn’t really work, but it led to several other compelling contraption drawings of funky invented objects that are funny/sad sexual surrogates.

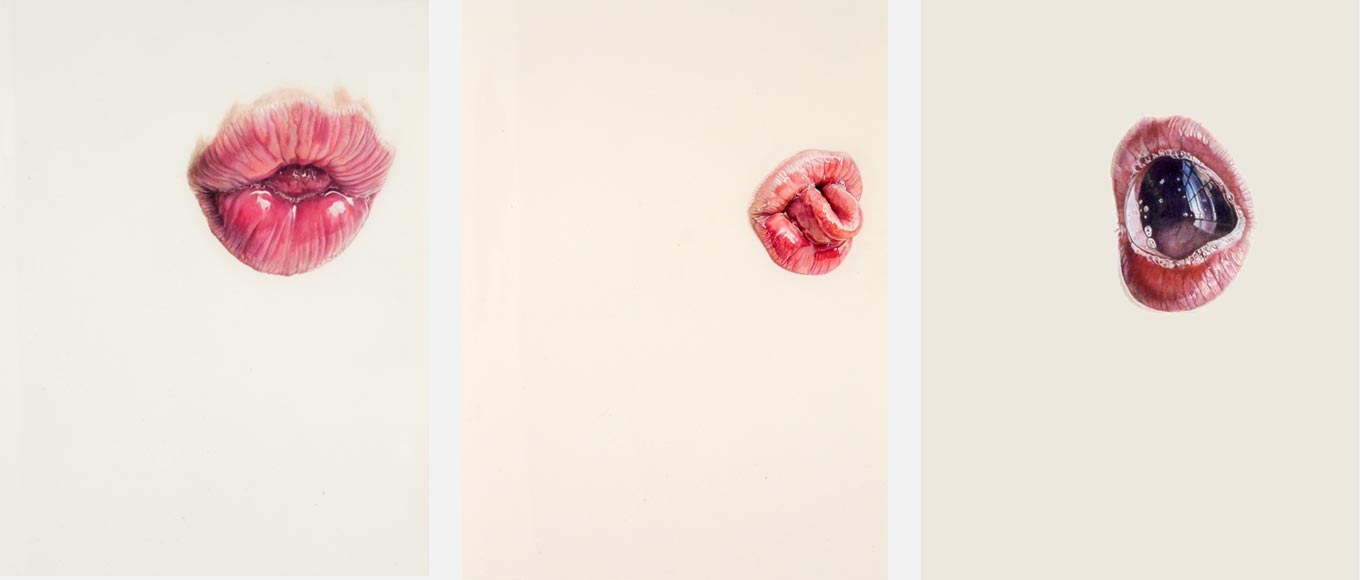

I also did small colored pencil drawings of mouths and tongues, intended as studies for the Wheel. In my desire to avoid stylizing, I was trying to learn exactly what a mouth and tongue look like. I ended up liking this nerdy project; the drawings that resulted were funny, sexy and gross all at once. That original exercise became a series, Lick Line, which sustained me for two years. Saliva bubble drawings, with various landscapes in the reflections followed. Several years later, I revisited the bubble concept in the series Blown: drawings of bubblegum bubbles in various stages of inflation and deflation, a physical manifestation of breathing, and another way to present the mouth in its absence.

Often an image or idea starts from deliberately pitching the visual against the verbal, so that the “meaning” of the imagery is changed or layered.

Compact

Colored Pencil on Paper

38″ x 50″

2004

French Kisser

Colored Pencil on Paper

38″ x 50″

2004

Sources outside of my own head inspire me. Looking at things I love often sparks my imagination: botanical drawings, natural history museums, decorative arts, and medical wax sculptures (and other artists’ work, of course!). I love puns – verbal and visual – and they are frequently the genesis of my ideas for drawings. I adore double-entendres. Often an image or idea starts from deliberately pitching the visual against the verbal, so that the “meaning” of the imagery is changed or layered. I want my audience to have a sense of surprise, and this is not always easy.

Although my drawings appear to be very realistic, many of the images don’t really exist, and are cobbled together from several sources (for example, the reflections in some of the spit bubbles I draw). I like working in a series, because I don’t always “get it right” or exhaust an idea immediately. I often need to try to hit the same idea from a slightly different angle.

Black Grape/Cotton Candy

Colored Pencil on Paper

18″ x 24″

2012

Just over a decade ago, I never would have imagined that my work would look the way it does. Although I have always been interested in drawing, I got my Masters in Fine Arts in printmaking, and the types of marks I made were gestural, active, process-y. I was interested in figuration, but my narratives were more heavy-handed (expressive was a comment I heard often). I still have images of these earnest, post-grad schoolwork, which I really enjoy looking at – so much more immediate than what I do now.

However, there are plenty of consistencies, content-wise; my work over time has always addressed female erotic experience, and the pleasure and discomfort of female desire. The intersection of sexuality and humor continue to compel me. When I was 22, I lived in Paris and I drew a series of narrative images that featured a recurring female character having trysts with her paramour – a baguette loaf. I bring images from that series into my class, to show my students what I was making at their exact age, and how my work is both similar and different now. My husband, who is also an artist, has a theory that all artists have one or two major preoccupations during their lifetimes, and that our entire studio practice centers on revisiting, reconfiguring and retranslating these original impulses. I think he may be right.

Various from Lick Line series

Colored Pencil on Paper

12″ x 16″

2004