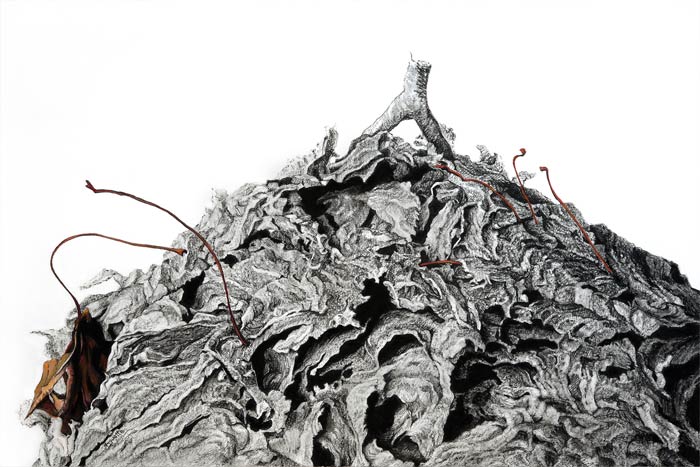

Red Stems, 17 x 11.25in, Charcoal and Pastel on Paper, 2013

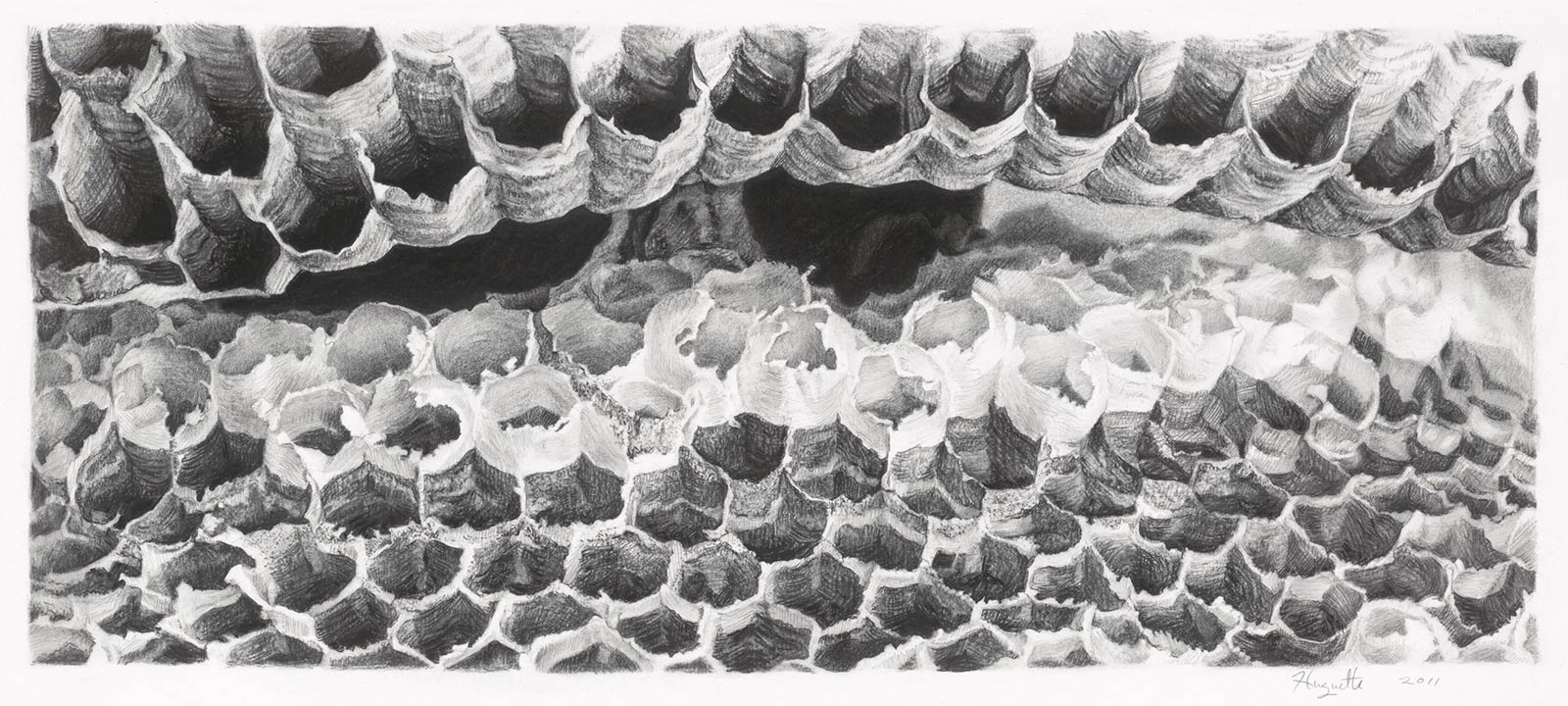

My interest in hornet’s nests and their material and construction is more than passing, as I studied paper-making (under the superb Michelle Samour) for a year-and-a-half at the Museum School in Boston. I have created sculpture from my own handmade paper, and so I am well versed in its properties. The nests are simultaneously simple and deeply intricate, their structure is both hidden and in plain sight. They are constructed of true paper – in that a fiber (rotted wood or plant stems) is pulped via maceration with saliva, and laid down in hundreds of thin contiguous strips forming a strong, light, self-insulating envelope. That evolution has come up with this ingenious and dimensionally viable solution for sheltering the young of a species is something I hold in awe!

As soon as I thought about drawing hornets’ nests, I realized they actually hold a personal metaphoric tie to me. I was brought up by a strong, isolating and difficult mother. The nest of the Dolichovespula Maculata (aka. Bald-faced Hornet), my main subject, is established by a single, bigger-than-everyone-else, queen. Beginning to end, she drives the action – producing a literal “caste” of characters. There are the female workers who are hundreds of identical sisters, and do all the construction, food gathering, protecting and child care. And then the stingless drones – who late in the season fertilize the new young queens (living only three weeks for their trouble). These young queens then then fly off, over-winter, and emerge to establish new colonies the next spring. I am intrigued by the idea of a hidden domestic world: An efficient household and nursery, entirely female-run, very active and real, where the only “expectation” is to replicate other, equivalent worlds.

I am intrigued by the idea of a hidden domestic world: An efficient household and nursery, entirely female-run, very active and real, where

the only “expectation” is to replicate other, equivalent worlds.

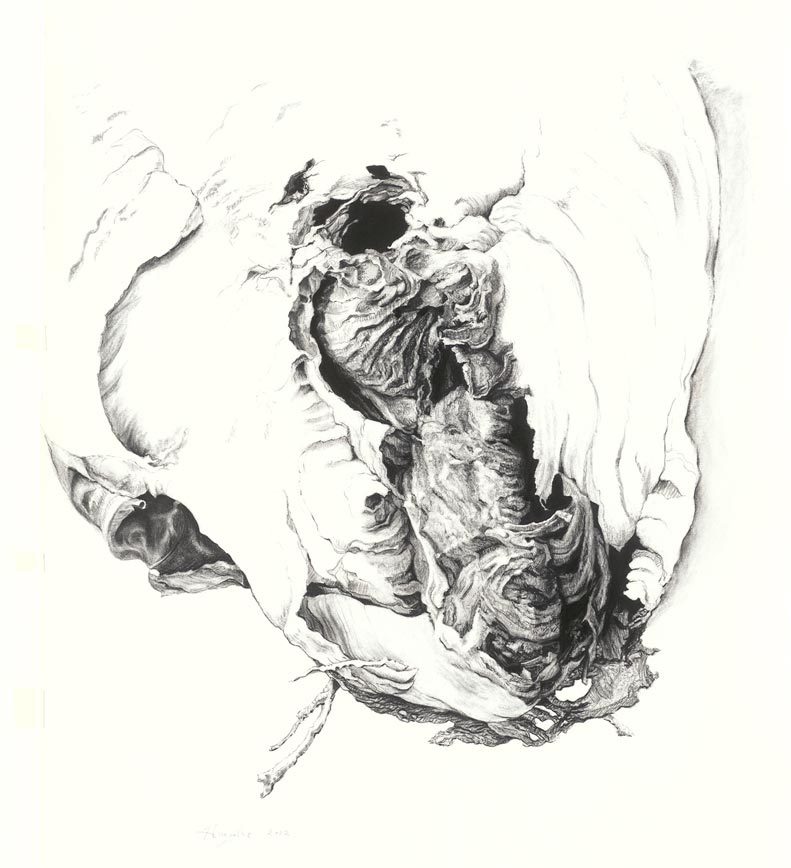

Enter Here

19 x 25in

Charcoal on Paper

2012

But that is just one thought about why I am compelled to draw these nests. Others come to mind, like the idea of space travel, space stations and colonization, architecture, robotics, war and ecology. I’m also interested in the anxious fear so often associated with these things. Yet, upon study, one learns that the creatures constructing these nests are unfortunately misunderstood, irrationally persecuted and under-appreciated for the good they actually do. In fact, they consume harmful insects and help pollination. As someone with a deep love for the natural world, I’d like my work to help replace the autopilot exterminator company mentality toward hornet and wasp colonies with more curiosity, wonder and respect.

I want to show people something they typically know little about, and nearly always associate with fear, and reframe it in an entirely different way

I have found that people tend to stop longer to look at a hand-drawn image than they do to study a photograph of the same subject. There are so many superb nature photographs in our everyday world, I feel their artistry and technical perfection are often taken for granted. With the hornet nests, I want to show people something they typically know little about, and nearly always associate with fear, and reframe it in an entirely different way, i.e., peel back the layers and reveal the ingenuity, the brilliance, and the beauty of these familiar, though curious structures. Representational drawing is ideal for that. The hope is that a drawing takes viewers past the surface, past the “oh, that’s a picture of a hornet nest,” toward an experience they will remember. Pausing to take in not only the ostensible subject, but also how its imagery is constructed, gives time for associations to surface to consciousness.

Many people upon viewing some of these pieces, have told me related stories or childhood memories. I’ve thought about collecting some of these and somehow incorporating them into an exhibition with this series when done. I have a few ideas, but nothing firm. I am happy if some viewers experience a feeling that they themselves could be a member of the colony, or at least that they can enjoy a nice, safe visit for as long as they wish. In this case, realism can help facilitate flights of fantasy. I’m OK giving viewers easy entry to my work via “accurate” representation because even though most don’t realize it, there’s still a great deal of selection, abstraction and interpretation going on. For that reason, clear evidence of mark-making in these works is important and quite intentional. From a distance, my drawings can seem photographic, but a foot or two away, they look like what they are, handmade drawings.

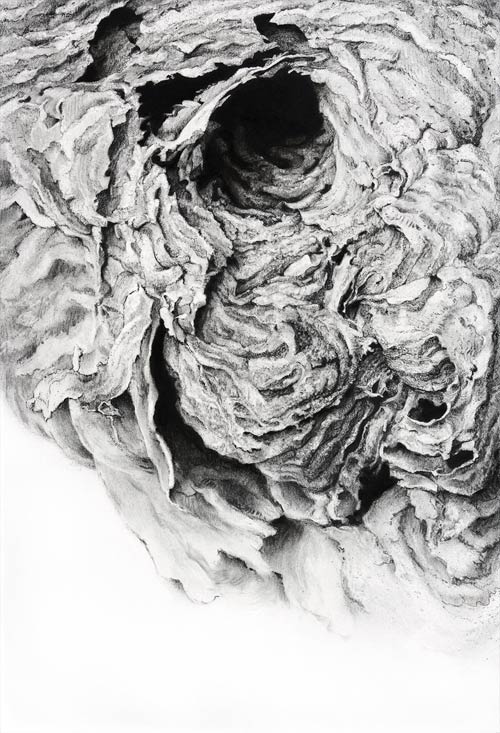

Mother Ship

44 x 55in

Charcoal and Pastel on Paper

2011

A Question of Color

Working exclusively in black and white since 2005, I introduced a bit of color in Mother Ship in 2011. That decision was organically grown out of what the piece needed. There was an actual leaf that still had its fall colors protruding from near the top in the original reference nest. I decided that if I didn’t depict it in color in my drawing, no one would ever notice that the hornets had woven that leaf into the structure of their nest. Without clearer differentiation, the rendered leaf would not only meld into the surrounding details, but it would end up appearing as a confused passage. Putting the color in was a gamble, but not a terribly big one. I tested the effect on a tracing paper overlay and let it live in place on the drawing a few weeks while finishing all the black and white portions. I could study the effect every day before committing. The last thing I did on Mother Ship was render that leaf in pastel. My main concern was that the color would call too much attention to itself and thus distract from the bigger picture. Balancing the color so that it was neither too stridently vivid nor ineffectually muted, was a way to manage that. Since then, every single comment I have received concerning the color in Mother Ship has been positive. From that point, I decided that other pieces in the Paper Nest Variations could also benefit from judiciously placed color. Use of color in this way can’t be arbitrary. It has to somehow advance the thematic scheme of the individual piece and also fit the series. Progressing in this vein, I am now working on a hornet nest piece in which large bold areas of color figure prominently. Everything stems from what comes before.

The Cosmic Muse

Intuition is what moves me to select both my series’ themes and individual subjects within those themes, and that intuition arises from the sum of my life experiences. So, occasionally, an insight might arrive in an instant like the proverbial “bolt from the blue.” But the closer truth is that my radar was set, ready to receive, and at the right moment the message could come through and be recognized. For this to happen, one needs a solid sense of what one cares about, trust that intuition will eventually supply the needed spark, and of course, the patience to wait. And while waiting for said inspiration, one should always be working! These days, I know in a very deep way when a subject is right to work on. But it took many years to arrive at that place.

I trust my instincts 100 percent, but while honoring this intuitive connection, I also evaluate my options rationally. I am thinking, with all of my accumulated knowledge and experience in art-making, “Will this work? What problems might I run into?” Most of those thoughts move to the technical issues I might face. For instance, I want the work to be challenging to execute, but not defeating. I’m well aware of my limitations. Some concepts or subjects might be better served photographically, as was the case with the paper nest Satellites series. Once I’m on a track, the work usually proceeds in a workman-like fashion, which I find very satisfying. The way I work is systematic, solving problems as I go, whether using photography or drawing. With the charcoal drawings, working from my own gridded photographic reference (or real world subject), I execute a light, detailed line drawing in vine charcoal to position the essential shapes accurately on the page. Then I work mostly top to bottom because that is what makes sense with charcoal. I keep the white paper clean as I go and use no cover-up whites. I always have classical music on as I work.

Portal II

12.75 x 18.75in

Charcoal on Paper

2012

I get a lot of satisfaction in the process and production of these pieces, those are my moments of zen, where the craziness of the world falls away and I can just live in the moment inside the world of the drawing.

I get a lot of satisfaction in the process and production of these pieces, those are my moments of zen, where the craziness of the world falls away and I can just live in the moment inside the world of the drawing. I have about 10 Bald-faced Hornet nests in my studio in various states of wholeness and disassembly in boxes, on a table and hanging. Visitors (mainly during New Bedford Open Studios) are intrigued when they see them and often ask questions about the critters, which, it turns out, are actually a larger colorless genus of yellow-jacket wasps, “hornet” being colloquial. Researching what I draw has become an important part of the process, and I enjoy being able to tell viewers a little bit about the nests and their makers. The informal education aspect built into the series is important to me. In another life, I might have been a pretty good scientific illustrator, but this more aesthetic approach fits my temperament and has the potential to reach a wider audience.

Pass Through

34 x 27in

Charcoal and Pastel on Paper

2012

Creative Growth

There have been many difficulties along the way, but I’ve learned to deal with them one by one as they come along (and still do). What’s important is that I never gave up. Art-making in some form has always been with me and is integral to every aspect of my being.

I will say that for the better part of my life, I struggled to obtain appropriate art education and it came to me very, very late. My five-plus years at the Museum School in Boston gave me the necessary time, support and context in which to locate my creative voice. By the time I arrived there, I had already learned the technical skills I needed through a wide range of experiences acquired with each move while following my husband’s career. The most pivotal of those experiences was a year studying at a small classical atelier in Baltimore, the Schuler School of Fine Arts. Being at the Museum School was about first determining the most personally compelling content for focusing the work, then finding the best format and visual language for that expression. It took a whole lot of thinking, sorting, sifting, trying and patience – a long period of intense growth. But the effort resulted in that I am now completely confident about my direction. Those years allowed me to find emotional connection and bring strength to the work not previously possible. Everyone has to find their own way, and that was mine. I’ve only just started making meaningful art since 2005. My challenge now is to fly with what I know for as long as I can.

Those years allowed me to find emotional connection and bring strength to the work not previously possible.

Vacancy

27 x 16in

Charcoal on Paper

2012