Black and White Rainbow #2

Wax Pencil on Paper

36 x 24in

2013

Over the years of making art I’ve told myself many stories about why I do this. But at this point in my life I find there’s one small story I wander back to more than any of the others.

When I was 18 and in my first semester at Oberlin College I took an intro drawing class. It was my first encounter with real artists, and I was completely mystified by my professors. I was so unformed, and uninformed that I would take everything presented as successful, worthwhile, brilliant. I had no filter, and I thought it was all “good” whether or not I could figure out why. This was in the early 90s and we were studying the second wave of feminism with Adrian Piper and the Guerrilla Girls, and reading Lucy Lippard. I saw slides of Ana Mendieta’s blood red Body Tracks and I wondered, bewildered, how I would make a place for myself. What can I do with this pencil that will justify my presence in this world with such big voices, attached to people who were doing such important things?

I was so unformed, and uninformed that I would take everything presented as successful, worthwhile, brilliant. I had no filter, and I thought it was all “good” whether or not I could figure out why.

Mélange, Wax Pencil on Paper, 24 x 24in, 2013

Tiptoeing with a Solemn Face, Wax Pencil on Paper, 10 x 10in, 2013

And in this class we were drawing the figure, going from two-minute studies to two-hour poses, and I finished the semester with large white pads full of horrible gestures. It was important practice, but at the time I couldn’t see that. I was trying to figure out how to be the next Kiki Smith, but I had no skills, and no ideas. However, it was here that I had one of my most important moments of insight. In a conversation with my professor about her path as an artist, she told me about a brief, quirky little job she had soon after graduating college as a scientific illustrator. She was working with a paleontology department at some university, and was tasked with drawing a collection of fossils. She completed just one piece – the tail of a fish embedded in sand stone that she could see only through a microscope. Bored, she explained it took her five weeks to finish, after which she quit to be a waitress.

A bomb went off in my brain. This was baffling. Five weeks?! That was half a lifetime to me. Why would these geologists pay you to do this? What was the value to them? What was it for? What did this thing look like? Her quick, matter-of-fact explanation was that her drawing was able to capture far more detail and information than a photograph could. And carrying this small statement, I have tried to make my way.

After that conversation I could see that it was actually possible for John Henry to have triumphed over the steam engine. It had seemed unimaginable that the hand and the eye could reach beyond the camera, or that science would ask this task of art. But I realized then, and understand more acutely now, that drawing allows a document to be made through painstaking labor, which can be produced in no other way. And through the process of patient observation one can gain a profound understanding. I find that my goal is always to look deeper, see more, and record as faithfully as possible.

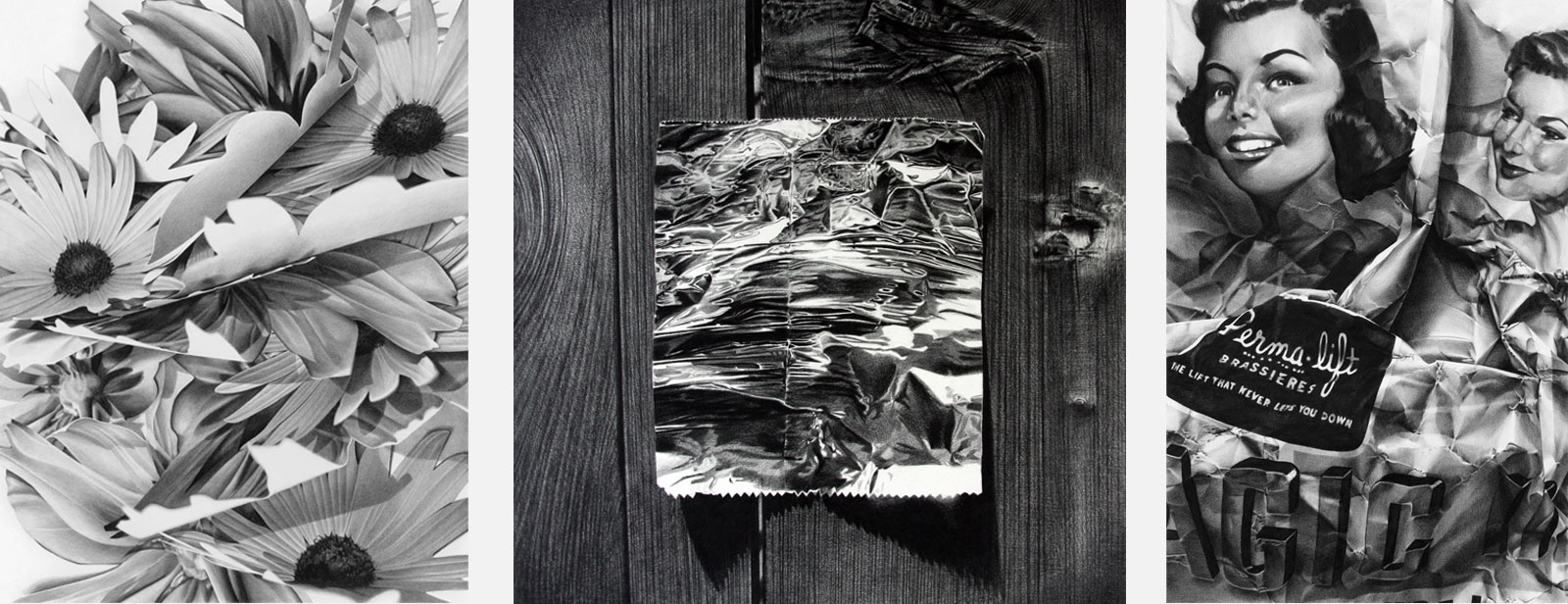

Sunflowers #2, Wax Pencil on Paper, 18 x 22in, 2013

Foil, Wax Pencil on Paper, 14 x 14in, 2012

Magic, Wax Pencil on Paper, 16 x 22in, 2013