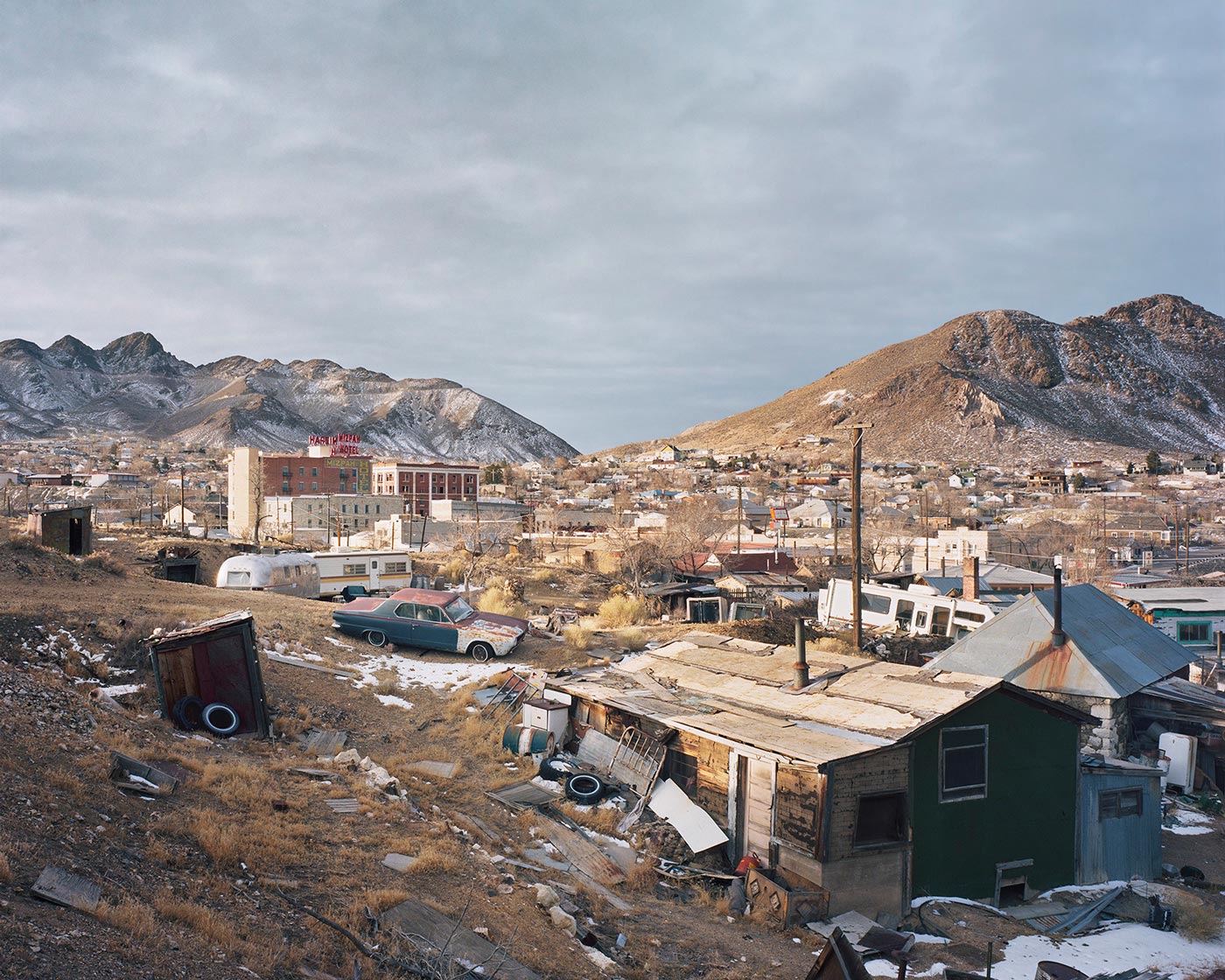

What was once the Wild Wild West—peppered with zealous gunslingers, courageous cowboys and virgin terrain—now lies the archaeological remains of the dust-laden American Dream. Bryan Schutmaat’s series, Grays The Mountain Sends, showcases that country-song-esque, lonesome west longing of simpler, better times through his subjects’ weathered eyes.

Homestead

Archival Pigment Print

Tell us a bit about your new series Grays The Mountain Sends.

It’s a project I made in small towns and mining regions in the American West, mostly in the Rocky Mountains. I met people and took pictures of them and their surroundings.

Growing up in Texas, were you surrounded by oil culture? Did that create your view of mining, or influence it?

I was raised outside Houston, which has a huge energy sector, however, I was surrounded by oil culture less than one would expect; no one in my family was involved in drilling, refining, or oil affiliated lines of work, etc. But when I was a boy, my dad worked in construction. I think the way he talked about work and about guys he spent time with on the job helped socialize me and shaped my view of the working class, and that’s what mining towns are made of. Mining towns interest me because a lot of them have fallen far from their glory years, yet continue to endure.

What role does your degree in history play in your work and process?

These photos have a whole lot to do with history, but honestly my educational background didn’t play a large role, and I didn’t do much research as I went about taking photos. Conceptualizing the project didn’t take more than a cursory understanding of the West’s history and Manifest Destiny, etc. So the specific reading and coursework I did during my undergrad degree relates in no direct manner. And when it comes to specific places and towns, I know very little, which might be irresponsible, but more than that it’s liberating. I always talk about the poet Richard Hugo and his influence on me. He said: “Knowing can be a limiting thing. If the population of a town is nineteen but the poem needs the sound seventeen, seventeen is easier to say if you don’t know the population.”

When it comes to specific places and towns, I know very little, which might be irresponsible, but more than that it’s liberating.

Ralph

Archival Pigment Print

Gold Mine

Archival Pigment Print

The two main focuses in Grays The Mountain Sends are the landscapes and the people, which set a rhythm for the series. In your mind, how are these different/the same, and what goes into shooting them?

Portraits and landscapes are inherently different kinds of photos, but I just consider them different pieces in the same puzzle, and this project is in many ways about the relationship between the two. The portraits are the ballast for the other pictures, giving the landscapes emotional substance to build on and add to. Viewers can find feeling and connect on a human level to a portrait and what they see in a sitter’s eyes; this feeling reverberates in a following landscape that has something to do with the world the sitter knows and his experience in life, whether true or imagined. I try to impart this not only by the content that bonds images, but how it’s aesthetically stated. I tend to make sequence choices based on visual associations formed from one image to the next, often relying on tone, texture, palette, light, repetition of shape, and further formal qualities. Using the camera to show aesthetic commonality between people and place suggests an emotional commonality as well.

Ellie

Archival Pigment Print

The portraits are all of men, apart from the very last image of the redheaded girl who is looking away. What is the role of gender in this series, and why are the men so predominant?

This isn’t a typical documentary project, and I’m not trying to give a full picture or tell everyone’s story, which would be impossible anyway. With just over 40 photos and 14 portraits, it’s a really concise series that’s fragmentary and entirely subjective – a small window into a vast and complex region. While on the road, I took many pictures of women, but when I began editing, none of them felt right in the sequences. Given the particular narrative I developed, I felt that pictures of women and their perspective ultimately didn’t add to what I was saying, and the vibe of series was more compelling with only portraits of men in isolation. Ultimately I feel this work is about the patriarchs of the American West and how we’ve reckoned with the outcome of imposing a very male-driven doctrine upon the bulk of a continent’s wilderness; it’s about the hopes, efforts, and failures of our fathers, not so much our mothers. And in some ways, I think I attempted to make portraits of my own father through these guys, reflecting on a father/son generational narrative and how that relates to the lore of the American dream. That said, I think I also just really like to photograph men.

And yes, the red headed young woman is the only woman in the series. She’s looking away because she’s not a protagonist in the story, but a character in the men’s periphery that brings small joy to the tedium of their lives.

Ultimately I feel this work is about the patriarchs of the American West… it’s about the hopes, efforts, and failures of our fathers… and in some ways, I think I attempted to make portraits of my own father through these guys, reflecting on a father/son generational narrative and how that relates to the lore of the American dream.

Cemetery

Archival Pigment Print

The photograph with the graves stands out to me, could you tell us a bit about it?

It’s an old cemetery in Tonopah, a mining town in the Nevada desert. You can see tailings from mining activity on the right, in the distance. The graves range from 1901-1911, which was a prosperous time in the town’s history. It’s said to be haunted, and ghost hunters have gone out there with equipment trying to find electronic voice phenomena and other spooky stuff. A woman I talked to while photographing was convinced that nothing I shot would come out and that the pictures would be blighted by orbs due to supernatural activity. She was a really sweet lady, even though it’s all nonsense. I like to think this photo resembles how the past weighs on the present, almost to the point of haunting. The West was shaped for better or worse by the efforts of guys like those buried there in the ground, who people say haunt Tonopah.

I’m always open to discovery and what the world offers; the best photos tend to be the scenes found by chance.

Your photographs have always been a great exploration of culture, with an unbiased narrative on your surroundings, is this something you strive for?

All photographers have a point of view whether or not they consciously attempt to convey it, so I don’t know if I can claim to be unbiased by any large measure, but I’m not trying to make any big statements. One of the cool things about photography is its ability to create atmospheres that viewers can step into, explore, and analyze independently. Good photos rely on the power of suggestion, but if it’s too heavy-handed, it has a negative result. I guess I feel like my photos should be more about the world than my opinions.

Buckmaster

Archival Pigment Print

Do you ever change what’s in the photo or simply not shoot it because it’s too much of a statement?

I was interested in making statements, but statements that were more introspective and emotional. I think there were a lot photos I didn’t take, and others that I took but later omitted, because the scenes were too strident when it came to socio-economic and political issues. It was never my intent to foreground politics or the broader economic crisis besetting America at the time the pictures were taken. Like anywhere else, the West has its problems– corporate influence, economic disadvantage, environmental devastation, and a deluge of social pathologies when it comes to meth use and so on, all of which would make good material for expounding on injustice and the exploitation of the land and the working class. But I steered clear of that and viewed things with a more poetic lens, hoping to move focus from societal problems to the problems we face inside ourselves.

Cafe

Archival Pigment Print

Are you a wanderer/searcher or are there specific images you know you want to make? Is there much pre-shooting and location search or is it an “I see and want it” type of situation?

There are a number of things I have in mind prior to shooting—themes, certain subject matter, motifs, locations. But I’m always open to discovery and what the world offers; the best photos tend to be the scenes found by chance. Pre-shooting is involved in a lot of cases, because I often find great places, take a few snaps on my DSLR, and then come back later with the 4×5 when the light is nice and sweet. Yet there are instances when all the stars are aligned at the exact point of discovery. Then it’s a mad dash to set up the camera and capture what I see, and when the shutter is clicked it’s a very wonderful feeling.

Derek

Archival Pigment Print

How do you approach your subjects?

Portraits are a little different though; I’d say I worked harder for them and there were more limitations. People come and go so I had to photograph them wherever I happened to meet them, in whatever light there was. Though sometimes I formed relationships and got invited to people’s homes, which are always excellent places to make photos, but that was the exception. I would approach my subjects in different ways. Sometimes I’d start up conversations in bars or cafes, and after some talk about the weather or whatever, I’d reveal that I was photographer and would like to make portraits. But more often, I’d ask to take the picture at the outset: “Hi, I’m working on a project about the American West…” Then there were magical occasions when an inquisitive local would approach me when I was under the dark cloth out making a landscape, and soon I’d turn the lens onto him.

You often have a recurring motif of “artificial nature” in your work. Why do you put such an emphasis on documenting these things?

As I mentioned, in a lot of ways this project is about the relationship between people and the land. These motifs demonstrate the West’s cultural identity and how it has been shaped by proximity to wilderness. The paintings and photos of the outdoors in Grays are important given how they relate to history and past perception. The idyllic landscapes that decorate the walls of homes and businesses across the West typically echo a 19th century style of painting and photography derived from the Hudson River Valley School. These images—the light, beauty, and abundance they encompass—implied a promise of freedom and prosperity to a young and hopeful nation. The narrative of photography in the West deals heavily with how this mythical promise has played out. So for me, depicting images of images helps to acknowledge the past and contribute to an ongoing dialogue. But this time, I’ve focused more on the individuals—the heirs of those who believed what the pictures told them.

Tonopah

Archival Pigment Print

Being able to see so much of America, and dig deep into culture, you must see such a variety of lifestyles. What are your thoughts on the progression of defining “America” in terms of values, technology, and humanity?

Wow, I could write a whole book on this. I’ll just say that in some ways we’ve progressed and in other ways things are the worst they’ve ever been. There’s not much reason to be optimistic about the future and I don’t know if we’ll be OK, but we’ll keep carrying on.

What do you think your photos mean to the people of this country, and what do they mean to you?

I made a portrait of a guy named Ken who worked at a truck stop, and I returned a couple months later to show him the photo, thinking he would think it was special. All he said was, “It looks like me,” then we both laughed. I really don’t know what my pictures mean to the people who call these small towns home. And I don’t think my work will ever be widespread enough to find out. To me, however, these pictures—and photography in general—means a great deal. It’s an indispensable part of my life that gives me vitality and fulfillment. So when someone takes time out of his day to sit in front of my camera, I really feel an enormous sense of gratitude, even if it’s no big deal to the sitter.

Any advice for young photographers just starting out?

You’re not special. Work hard.

Gunsmoke, Archival Inkjet Print

Joe, Archival Inkjet Print