Somewhere near the intersection of eccentric line drawings and architecture you’ll find the work of Kim Schoenstadt. Speaking with Dirty Laundry, the Los-Angeles-based artist discussed striving to create intellectually stimulating and visually beautiful pieces, along with the merits of relinquishing control and learning to embrace chaos.

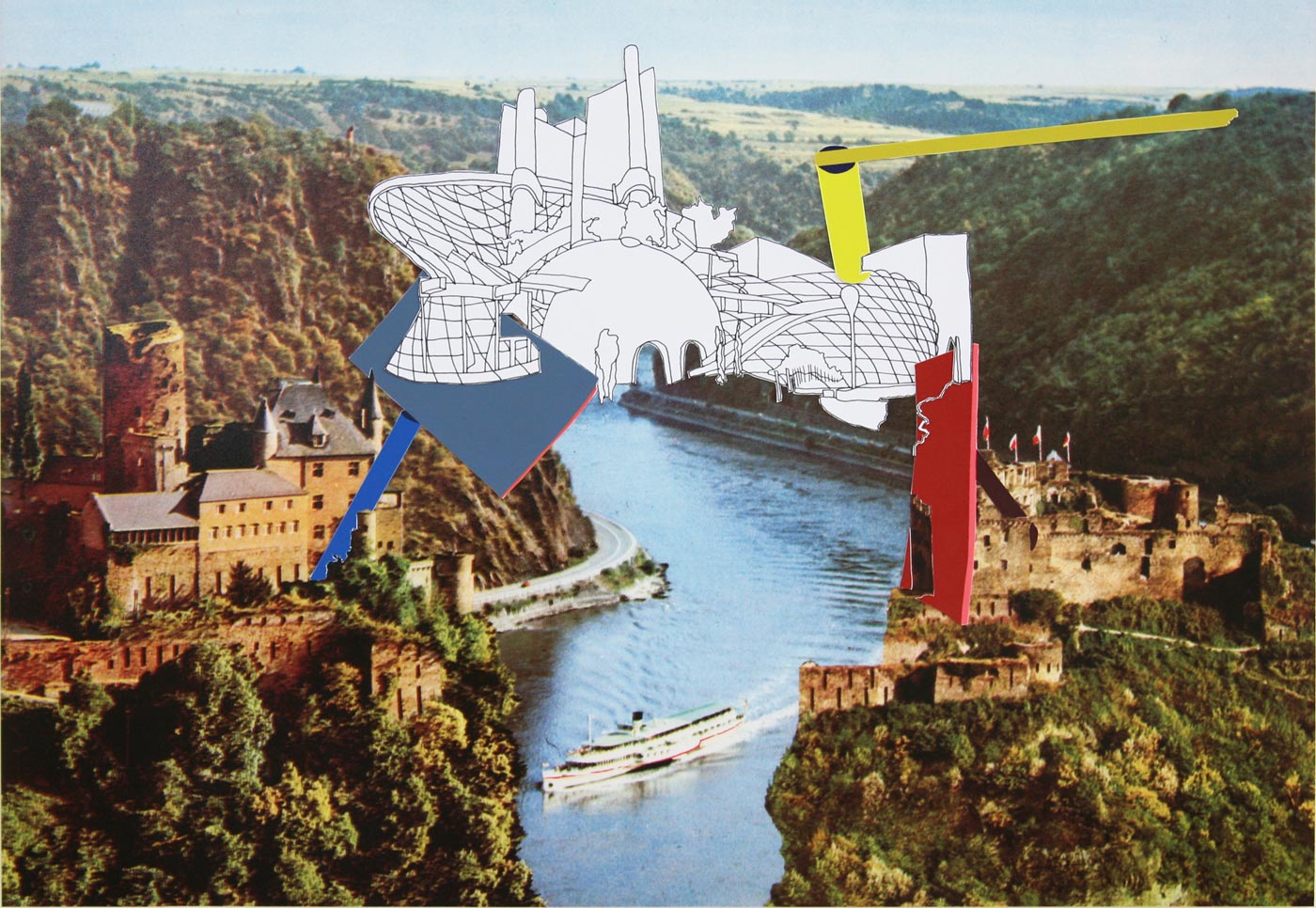

Sight Line Series: Frankfurt 1 Postcard with cut paper and drawing

4 x 5.75in

2012

What sparked your obsession with architecture?

It really began in 2004, when I did the Lodz Biennale in Poland. Lawrence Weiner was my selector and I called him and I said, “I’ve never been to Poland and I’ve never been in a Biennale, what do I need to know?” And he said, “Well they don’t have a lot of supplies or money for supplies, so bring everything you need, and don’t expect anything to get shipped back because they have no budget.” And I thought, “OK, great, I’m going to have to do something on the site.” So I wrote to the organizers and I asked them for photos of things they found interesting. I didn’t want to lead them in any way, I just thought “Oh, well I’ll start with whatever they find interesting.” And it was all photographs of architecture. And I realized, the sort of Soviet-Brutalist architecture was very vertical, and the California Modernist architecture was very horizontal, but they were using similar solutions to different problems. I just got hooked.

And the other thing I got hooked on was when the local people came into this international Biennale, and they stood in front of it, and picked out pieces of architecture that they knew. The funniest story is about this one guy standing in front of a piece saying “New York! New York!” And I’m saying, “No, that’s here, that’s right up the street.” And then someone translated, and he said “Yes, but we call it [the building up the street] New York.” It was this great moment where he was getting into the work… and I totally misunderstood it. But he was getting into the work based on something he knew and could pick out, and that was something I found really interesting.

I like to make a unique work for each show and so I don’t just have stock pieces that I just plug into wherever. I really study the location, I study the space, and I do a lot of research on the history and on the local architecture.

How important is history in the buildings that you choose, and what kind of research is involved?

That was really the moment that I started realizing there was more to the story than a pretty picture. So when I was invited to do the Prague Biennale the following year, I started really looking into the history of these buildings, and the story behind them. And I started mashing things up according to quirky little histories. Not that anyone would understand that, which is one of the reasons why I create a source-material list for each work. So on one side, it’s all pictures of the pieces that I’m using, and on the other side it’s the information about the piece of architecture. And I find that that’s actually really helpful for some people, because they can say “Oh right, that is that Niemeyer building or that is Eliot Noyes’ place.” That aspect I find very interesting. As for the research involved, that just depends on the location. I like to make a unique work for each show and so I don’t just have stock pieces that I just plug into wherever. I really study the location, I study the space, and I do a lot of research on the history and on the local architecture.

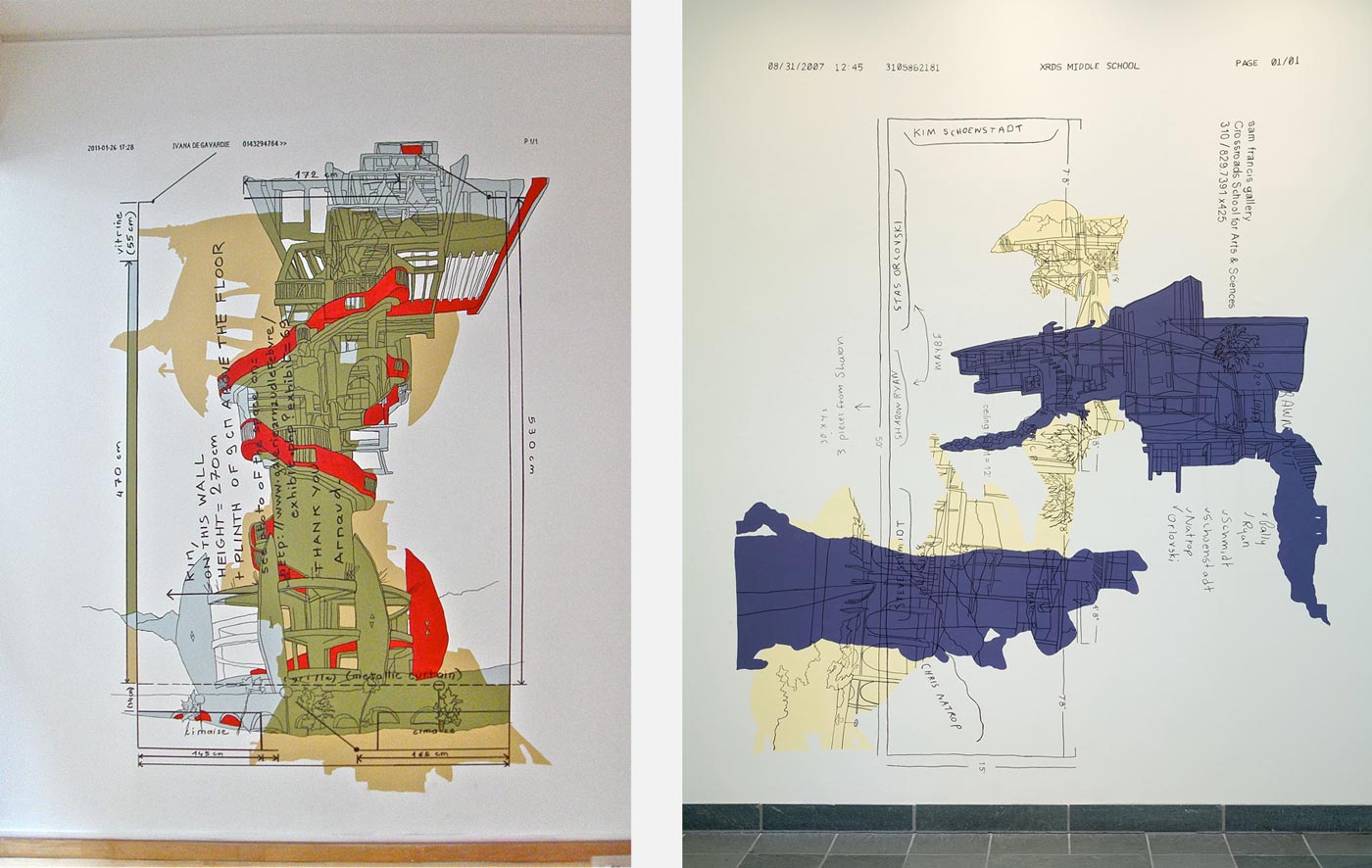

Fax Drawing: #9, Galerie Arnaud Lefebvre, Paris, Ink and Paint on Wall, 2011

Fax Drawing #2, Sam Francis Gallery, Crossroads, Santa Monica, Pen and Acrylic on Wall, 2007

What else goes into your process?

It starts with the research, and then the next step is selecting pieces of architecture that I find interesting. Then I make a freehand drawing from that. After that, I either scan that into the computer or I make a transparency of various percentages and sizes. I have a giant light table in my studio that I love working on. I usually just kind of pick transparencies and mush them around until something comes into shape. And then I make a drawing from that and I do a lot of editing on the drawing table. When I work on the computer it’s the same situation. It’s just mashing up. You know, you can scale in Photoshop much easier, and then erasing lines is a little bit more labor-intensive because it’s not just me drawing and choosing not to draw a line, I actually have to go in and physically remove the line that I want to take out.

So which one do you prefer?

I prefer both. They’re both good tools. One time I was traveling and I needed to keep working on a piece, so I had the piece on the laptop, and that works fine. With the new three-dimensional work, I need the computer. I need the laptop to do the 3-D modeling because I’m coming to it not as a sculptor, but as a person who makes drawings. So I use a 3-D modeling program to really help me see how the 3-D aspect is going to feel and move within the work.

Your color is very striking and unusual. How and why do you make the color choices that you do?

That’s a good question. Mainly I start the work by kind of blocking-in certain hues, and then I tweak. So I’ll just start thinking “OK, I want something warm here, I want this one to be cool, or I want to riff off of this color in this photograph. And then I start building it. I like triads, because you can have two things that agree and one thing that really disagrees and that throws the whole thing off-balance, and I kind of like that. Because like the drawings, which are sort of mashing up balance and imbalance, I like the color to do that too – to spark and create a distraction.

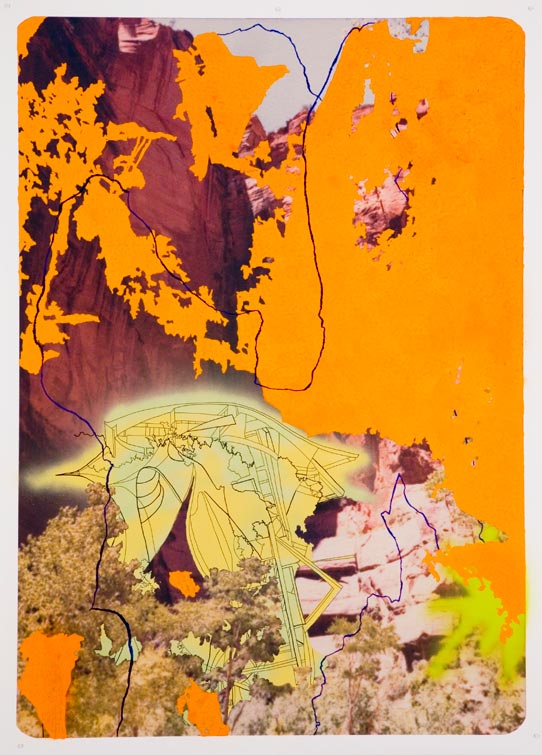

Lake Powell Series: Site Plan 4 (Orange)

Archival Inkjet Photograph with Spray Paint, Pen, Oil Pastel, and Gouache

47 x 34.25in

2007

I was just kind of stuck and I couldn’t think of what to do, and I was going to be there for a week. So I decided to construct a project based on instructions and check them off one by one.

What’s the relationship between chaos and control in your work?

Well that really started a while ago. It started back when I was trying to integrate color into my work. And I had been doing these really intensive, intricate little line drawings and I wanted to figure out color. Because, like I said, I’m not a traditionally trained painter. So I didn’t take all the color theory classes, I was really obsessed with drawing. So that was something that I had to learn much later on. My first concept was that I would create a situation. It was for the New Langton show in San Francisco in 2006 and the concept was that you were squatting at New Langton. And the idea was that I would create a project over a whole week and people could drop in and see the progress, see how it’s going, and participate. I decided that I wanted to do this line drawing out of tape and then I would spray paint over it. I needed to know what I was going to spray paint, so I decided to invite people to tell me what to do. I was just kind of stuck and I couldn’t think of what to do, and I was going to be there for a week. So I decided to construct a project based on instructions and check them off one by one. And so I sent a letter out (a very boring letter) that said I want instruction for a word, a shape, or a mark, you can be as specific or non-specific as you want. I had never done this project before so nobody knew quite what to expect.

Can Control Eindhoven (Temporary Empire),

Spray Paint on Canvas with Vinyl Cut

25 x 68ft

2007

I got a fantastic response. Nearly 100 percent of the people responded and sent me instructions. And it was really actually quite fun because some people were creative with their instructions. Like Jens Hoffmann gave me this really complicated instruction, and I kept thinking “OK, this one is complicated, I’ll just put it off to the very end.” And in the end, it was a very complicated way of telling me to make a smiley face. That was really super because it was a really wonderful exercise in giving up control, and giving up that aspect of the work. So I really enjoyed that chaotic insertion, and I thought that the work was truly a success because you had all these different voices and yet it visually made sense. It really worked as a project.

Then I was invited later on to re-do the project in Europe at the Van Abbemuseum and I was feeling a little bit more comfortable that this experiment would actually work. Going into New Langton I thought, “Oh, if I get no responses, then I’ll just kind of figure it out.” But I was treating it like an experiment site and it worked out and I enjoyed that.

When you get these instructions, do you filter them or do you do whatever they say? Do you honor everyone’s request?

I do whatever they say. And the only time I didn’t honor everyone’s request was at the Van Abbemuseum because we literally just ran out of time.

Odd Lots Series: Hartford/Fiction,

Ink, Acrylic Paint and Vinyl on Wall

Room Installation

2010

What other participatory projects do you have?

Well there are many. I enjoy that aspect of making work. I enjoy creating projects that engage people in the process, and one of the things that I really love about making wall drawings is that I don’t close the exhibition in preparation for the opening. I don’t close off the gallery. I don’t hang a cloth and say “I don’t want anyone watching me,” I actually invite people to come in and check it out and talk to people about it. I remember when I was doing an installation at the MCA Chicago, it wasn’t an audience participatory work, but the space was open to the public and there was other work in the other wing. It was this long hallway exhibition space. And on one side, there was this really great Paul McCarthy piece and people were coming up to see it. The only thing between the public and me were these stanchions. And I remember one day this guy came in and was watching me for a while, and I went over to him to ask if he had any questions, and he said “Yeah, can I bring my class to watch you work? I don’t think they’ve ever seen a real artist working.” And it was fantastic. He brought all of these kids and it reminded me that we do hide this process, it’s not something that’s on public display that often. And that’s one way that I see my practice as engaging because I don’t like to hide that.

I enjoy creating projects that engage people in the process, and one of the things that I really love about making wall drawings is that I don’t close the exhibition in preparation for the opening. I don’t close off the gallery. I don’t hang a cloth and say “I don’t want anyone watching me,” I actually invite people to come in and check it out and talk to people about it.

But I also do create specific participatory projects. One I did in Salt Lake City called Color By Numbers and Shapes was for my Catherine Doctorow prize. I couldn’t help myself but to suggest that I create a whole new project and it turned out so fun. The idea was basically the same concept: I do a drawing, it gets translated into vinyl tape and then it’s put onto the wall. And then this time, we went one step further where we went into the back room of the museum and we dragged out extra paint buckets that had been used in previous exhibitions. And we just painted squares of each color, and then numbered them one through 10. There were instructions on the wall and a gallery attendant with a bucket of chalk. Anybody who came to the show could take a piece of chalk and draw whatever they wanted on that wall and then number it for whichever color they wanted.

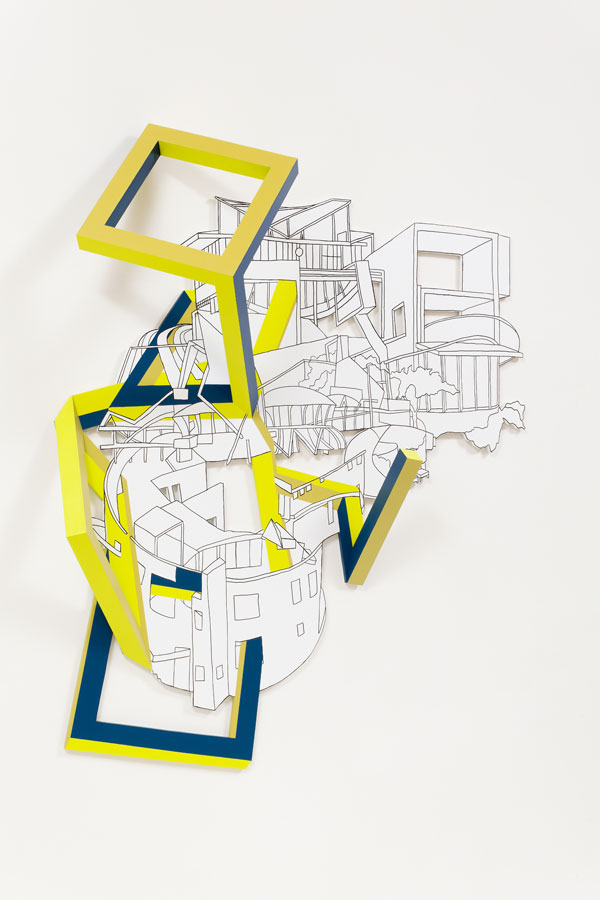

Parallel Version Series: Los Angeles

(with incomplete dimensional objects)

Pen and Paint on Wood with Dimensional Objects

60 x 60in

2013

At the end of each week, there was a team of volunteers that came in and painted by number. So if the heart had a number two in it, it got painted red. If the shoe had the number three in it, it got painted green. And it turned out so remarkable. This was another moment where it was sort of an experiment. I thought, “Is anybody going to participate? How is it going to look in the end? I mean, it could be kind of a disaster.” But it really was quite beautiful, and it really was a true reflection of that city, and what they wanted to convey.

As an artist, do you have a certain responsibility to your audience?

Yeah, I think any artist has a responsibility. I think that it’s a conversation. I don’t know that my feelings of responsibility are different than another artist’s feeling of responsibility. I think that one should have a feeling of responsibility to whomever you’re communicating to.

You seem to be making art for your audience, as opposed to artists who get ideas and just create for themselves.

It’s both. When I do a wall drawing, I’m definitely making the work and installing the work and people get to come and look at it. When I’m creating an installation that’s going to ask people to participate, I just think back to my 10-year-old self and want to create something for her. It’s fun. The best situation is when you can do both, when it’s a little bit of everything. Because the best pieces of art for me, are both intellectually stimulating and visually beautiful. And so if I’m making a wall piece, I want it to be engaging, even though you can’t always physically engage.

Odd Lots Series: #08

Ink, Spray Paint, Acrylic Paint on Bristol

19 x 24in

2011

[My teachers] were my greatest influences because they really taught me to throw out any previous ideas that I had about what an artist is or what art is, and just look at what I want to do.

Who are your biggest influences as an artist?

I have to say that my greatest influences were my teachers. There are definitely artists that I riff off of, but the greatest influences for me were the people who changed the way I thought about making art and enabled me to kind of go with both creating an intellectual project and continuing my stimulation in terms of thinking about projects, and researching projects, and enjoying that aspect. The people who made that be OK were my greatest influences because they really taught me to throw out any previous ideas that I had about what an artist is or what art is, and just look at what I want to do.

Can you tell us a little about the Art Not Ads exhibition here in DC?

Sure, that was curated by Nora Halpern and Welmoed Laanstra. That was a really fun project. Basically the concept of the project was that they hired trucks, one had visual artists, one had poetry, one had video. And they would run all around DC for a weekend. I was one of the visual artists and there was also another local artist who was a visual artist who participated, Maggie Michael, and also Ian Whitmore.

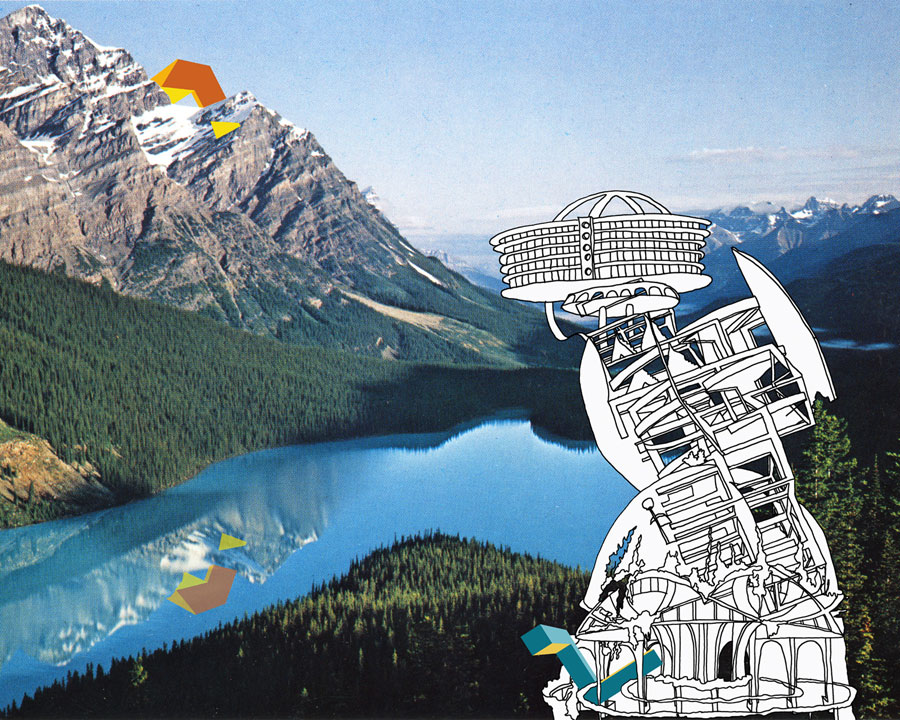

Closer to Nature Series (Mobile Drawing): Falling Water

Digital Print on Truck Tarps

10.5ft x 22ft 8in

2006

This was a really fun project because again, going with my more experimental side, it presented a lot of really cool challenges. Like when you have art that’s moving, what kind of art do you put on it? It can’t be too complicated and it can’t be too simple. And my understanding of DC is that it’s kind of a town where a lot of conversations happen. You don’t want to yell at your audience that gets yelled at all day. So I thought, OK, I’ll go the opposite. I’ll just give them something really super pretty to look at. Something idealized.

My husband and I just visited Portland, OR, so one of the photos is actually of this beautiful, still pond from the Portland area. And then the other image is actually this gorgeous waterfall from Iceland. So that was the basis of working off the photographs, but then I thought, “Well, I have to add something to it,” so then I just started inserting all of my architecture into it and kind of riffing off of the Frank Lloyd Wright Falling Water house idea. And then I ran around the mall as it was driving around, documenting it in all these strange positions.

Closer to Nature Series (Mobile Drawing): Still Pond, Digital Print on Truck Tarps, 2006

Closer to Nature Series (Mobile Drawing): Falling Water, Digital Print on Truck Tarps, 2006

So what do you think about the architecture here in DC?

I think it’s actually pretty amazing. Some of it is very uninteresting, and some of it is pretty awesome. I’m kind of obsessed with the FBI building because it’s just awkward in so many ways, and it probably has the most security cameras I’ve ever seen on a building. It has this sort of raised floating thing. There’s so much about it that is so interesting to me. There are so many areas of DC. And I happened to be there when they were replacing a pane of glass. It was mesmerizing because it was this big modernist box in the middle of all of these ornate buildings. And it’s doing the same thing that everyone else is, you know, you break a window, you gotta replace it. Except to replace this one, apparently you need six cranes and an entire city block closed-off. It was really beautiful. That entire installation process was very choreographed.

I specifically chose the Air and Space Museum because I wasn’t entirely sure what I was going to find there. I was pretty amazed. Their archives are incredible.

You recently received the Smithsonian Artist Research Scholarship. The public only sees the tip of the iceberg with the Smithsonian collection, but you were given access to the rest. How was that experience? What were you drawn to?

The experience was pretty amazing and daunting. Because it is so huge, the idea of narrowing down what to focus on and what to study is pretty difficult. Because you want to create a project that’s open enough to give you latitude to explore and see where you go. But at the same time you want to take advantage of what you can actually get your hands on. And so that was really amazing. I specifically chose the Air and Space Museum because I wasn’t entirely sure what I was going to find there. I was pretty amazed. Their archives are incredible. Because of all the budget cuts and whatnot, it’s fairly difficult to pull a unique object. So I was able to look through all the documentation, which works perfectly for me because that’s generally what I work from to begin with. And what I came across and got sort of obsessed about were these parachutes that made sure that the Apollo missions and the Gemini missions got back to earth safely. And I got really fascinated at how hard it is to actually get somebody into space, and all of the logistics involved and all of the different types of rocketry and fuel tanks, and all of these things. And then to bring them home? It’s a parachute. Like, they just drop out of the sky, launch a parachute, and float back down to earth. And there was something really poetic and beautiful about that.

How will your experience with the Smithsonian impact your future work? Do you have any new ideas stemming from it?

It will impact my future work, but I still have to unpack the hundreds and hundreds of images I took. So that’s going to take me a while. And integrating that into a whole new body of work is going to take a while. But I’ve already actually started drawing the parachutes. I’m really excited about them and I’m looking into different ways of drawing them as well.

What do you hope people take away from your work?

I think my hope is that they can see things a little bit differently. The way I’m able to build architecture off of each other in impossible ways. One of the things about my work is that I don’t have to pay attention to gravity. And architects do. To build real situations, you have to deal with “OK, if I put this here and this here, that might fall down.” I don’t have to deal with that, and I think that’s a freedom that I really enjoy, and one that I hope people will take away from it. You don’t always have to draw a nice clean box, and you don’t always have to find one solution, there are multiple solutions to every problem. Just think about how things build off of each other and sometimes you can zag and that gets interesting.

Any words of wisdom for emerging artists?

I think my advice is: Learn everything that you can learn, and then go and work for another artist, and learn everything you can learn, and then probably throw out the first half of what you learned. Go and see as much art as you can, and just follow your gut. And follow what you want to do because one of the biggest inhibitors for me when I was starting off was my own ideas about what was right and what was wrong, and as soon as I figured out that it didn’t matter, it was a freedom that I find very valuable. That it doesn’t matter. That I can just do what I want and then figure out how to make it happen.

Sight Line Series: Switzerland, Spring

Archival Ink Jet on Paper

16 x 20in

2011

.