High school teacher by day and landscape super artist by night, Gregory Euclide chooses to surround himself with the source of his power – the natural world. His paintings and installations evoke fantastical landscapes absent of figures, but oftentimes their lingering footprint can be felt. The Minnesota man discusses his daily routine for work and play, plus knowing when to trust your intuition.

As If Muting the Land Was Part of Knowing

Mixed Media

26 x 19 x 9in

2012

Growing up, what was your relationship with nature?

I had a pretty magical upbringing. At first there was a neighborhood full of kids and several of us were only a day apart in age. Our birthdays were February 11, 12, 14, or something like that. We would build forts in the green spaces between the houses. When my parents built their own house in the country surrounded by farm fields, I was alone. There were no other kids to play with and there were wide-open spaces, ponds and tree lines to play in. It was then that I really started to build a relationship with the natural world. I spent every hour of sunlight outside, exploring, making and playing. Looking back, I can see a direct link from that time to my current practice as an artist.

I have learned that play is such an important part of whatever will become valuable in my practice. I have to build in time to make a mess and not fully grasp what I am doing…

Can you describe your daily practices and routine?

I have two ways of being: summer break and then everything else. During the school year I wake up at 5:40, put the water on and wash out the French press from the day before. I step out on to the deck and dump the grounds into the forest. Sometimes it is raining, sometimes there is snow, sometimes it is so cold that my hand sticks to the door, sometimes it is so clear and bright that I have to stop and stare up at the stars. With my thermos of coffee and a sack lunch, I head to work at the high school. Each day I have five classes, each with anywhere between 38 and 30 students. I teach my classes in graphic design, painting, drawing and introduction to art and head home. Once I’m home I put a record on and start work in the studio.

During the summer I don’t work at school, so I am able to see daylight, which is really enjoyable. In Minnesota, much of the year it’s dark when I get up and dark when I return home. So, summer and being able to spend time outdoors is really a luxury. During the summer I wake up, make coffee, put a record on and start working for 12-plus hours. This work is more like play. It is a time to experiment and therefore it doesn’t really feel like work. I have learned that play is such an important part of whatever will become valuable in my practice. I have to build in time to make a mess and not fully grasp what I am doing, or if I’ll get anything interesting out of the process.

Part of a Twisting I Built a New Narrative of Protection

Mixed Media

39 x 57 x 10.5in

2013

How does teaching compare to making?

It’s drastically different. Teaching is strange and it is done in a very strange atmosphere. The bells, the 2,000-plus students, concrete floors. All of it: strange. The students change every year and despite my best efforts to rotate the curriculum, I am essentially teaching the same skills over and over again. I refine my approach, offer advice and set expectations for certain outcomes, but at the end of the day it is just a lot of giving.

Making, on the other hand, is equally as demanding but it is on my terms – it’s very selfish. I’m doing in the studio what I want and not everything needs to make sense or follow a narrative. It is a very different way to structure time. What I find is that I end up working much harder and longer if left with no definitive cut off point or bell, but it is very scattered. In the studio I’m always working on several things at once. I might be making trees out of found materials, tearing the metal off of an air filter to see what that could be used for, or painting a traditional landscape.

What have you learned from your students?

I don’t even think I could put that into words. I think it is easier to say that I learn because of them, as opposed to explaining what I learn from them… if that makes sense. They are astonishing, independent minds looking for something to interest them – looking for something to care about. They are going through an amazing time in their lives. I try to keep that in mind when I am interacting with them. What do I learn because of them? Patience, respect for time, the need to remain plastic, the need to laugh and to be funny and most of all – it’s not about me.

They are astonishing, independent minds looking for something to interest them – looking for something to care about. They are going through an amazing time in their lives.

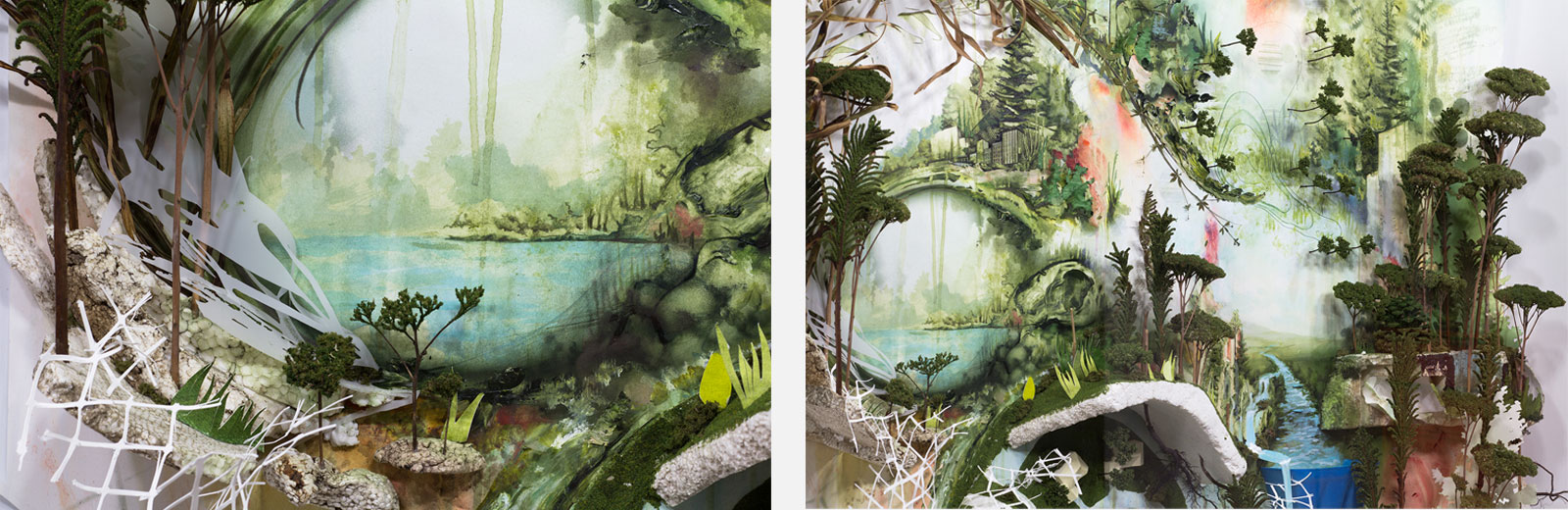

Detail shots from Diverted From the Valley and Restored for Your Holiday

Mixed Media

49 x 49 x 9in

2012

Talk a little about your choice of materials. What dialogue is created between the materials you’re using and the work itself?

My work is primarily about my experience in the land. Being an artist working with land, naturally, I was concerned about the history of how land has been portrayed and how it has been used to different ends in the tradition of landscape painting. I started feeling like I wanted to develop contradictions or confrontations in the work, probably because I was feeling these things within myself.

I grew up in a rural setting, where farm fields, tree lines and ponds surrounded us. I thought that was nature. What I didn’t think about as a child was that those trees and ponds were only there because they were the parts of the land that could not be farmed because they were either too wet or too rocky. The rest of the land was completely wiped clean to make way for cornfields. We just grew up thinking rolling farm fields are beautiful and they mean “rural” or “country” or “land,” and exemplifying what is natural. The subdivisions and the city were man-made and the opposite of that.

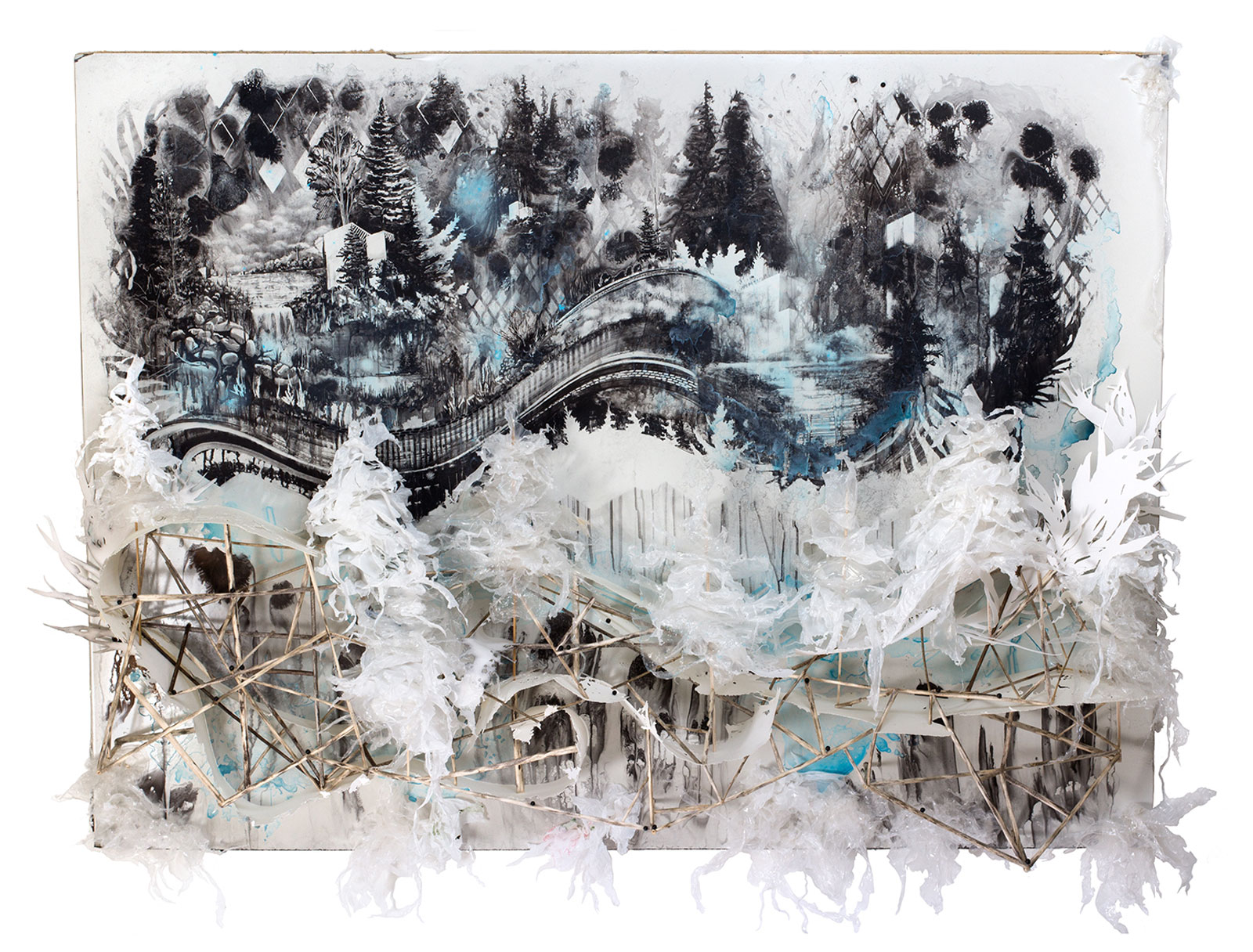

I Know Your Fences are Pools Passing Through Meaning

Mixed Media

2012

I wanted to create a similar confusion or complexity in my work between the created image, the rendered image and the actual thing. So, I started to place real organic matter in the scenes that I was painting. I was initially intrigued by questions like, “If the frame defines this work as a painting or a window to the world, then what does it mean if in that world there are both representational painting and the natural material that the painting is referencing?” Then I started to complicate the issue by using things commonly found in the natural environment that were man-made such as foam or plastic.

I have always been very deliberate about the materials and have tried to have dialogue between objects, that at first seem one way but turn out to be something different upon further inspection or further contemplation.

How have you brought the landscape inside the restrictions of a gallery?

The most interesting time I had with this was in Toledo at the Toledo Museum of Art. I was doing a large installation for the Small Worlds show and it included a lot of dirt, branches, and leaves. Everything needed to be dealt with by the conservation team. They put everything in bags and filled it with gas to assure that there were no bugs that were going to come into the space and eat a hole through a priceless work. It was quite the process.

How do viewers respond to the work?

I mostly hear that they enjoy the exploration of the work; that to see it in person and to be able to move their bodies around the work is a rewarding viewing experience.

Held Within What Hung Open and Made to Lie Without Escape

Mixed Media Installation at Museum of Arts and Design, NY

2011

Besides the natural environment, do you draw from any other sources for inspiration?

I am really intrigued by the history of land and land use. My work is just as much about the tradition of landscape painting and how land is portrayed in media as it is about my experience in the land. Books like Landscape and Power, Landscape and Memory, Storming the Gates of Paradise, Flight Maps and many others have allowed me to look at the issue from a number of perspectives.

Often at the time, I don’t know what I am doing… it just feels like I should be doing it.

How much of your work is planned, and how much is intuition/experimentation? Which is more important?

What I have found is that the play always becomes the work. What starts off as an experiment, or just something fun to do, always ends up being the next level of the work. Often at the time, I don’t know what I am doing… it just feels like I should be doing it. Then, later, it dawns on me why I might have done that. So, I suppose I really do trust my intuition. As far as an individual work, I never have a plan as to what a work will look like. The installations on the other hand are always planned out months in advance. They are simply a different beast that requires a certain amount of planning and preparation.

You have mentioned before that you don’t go to very many art openings, and you have an intentional disconnect with the art scene. Why is that?

Generally speaking, I don’t need the opening. I primarily prefer to view art in less crowed situations. Most openings I have attended are social events with very little to do with the art on display. I have never really cared for that scene.

Meaning Learned My False Floating From Propped Up Modes

Mixed Media

35 x 37 x 9in

2013

The artist has a history of living and working in heavily populated areas. What are the benefits of not living in a city as an artist?

I prefer open spaces and solitude. I can be outside and feel like I am alone in the land. I learn a lot from being able to observe, whereas in the city I always felt like I was the one being observed. I have access to large plots of land that are almost untouched by development or industry. My closest neighbor cannot be seen. I’m in London right now for an opening at StolenSpace Gallery. Last month I was in Paris for an opening. I get out to see some of the biggest cities in the world, but when I am at home I want some quiet. The benefits of not living in the city are clear to me; on my five acres of land I feel connected to the world in a way that is not just about humanity. In the city the land is manipulated to extremes to serve the people who live there, even the “natural” spaces such as parks have grounds crews and park boards.

What is the importance and significance of breaking boundaries in life and art?

I think one just needs to be honest. If you are making a painting about your experience in the land and you get to your studio only to find rectangular sheets of paper – I think it is valid to ask, “does my experience fit on a flat sheet of paper with two measurements or do I need to do something else to best convey what I want?” It is not inherently important or significant to break boundaries.

Where do you see your art going?

More. The best way I can describe it is more.

You talk a lot about music, and it’s evident in your work. How important is music to your creative process, and who are your top five musicians?

I will give you five that I have been listening to in the past month, but they’re not necessarily my “top five,” because that is too difficult for me. The latest albums by all these artists are really impressive.

1) Julia Holter

2) BVDUB and Loscil

3) Tim Hecker

4) Takeshi Nishimoto

5) Rauelsson

What’s the best way to end your day?

With some friends around a fire.

There Are Paths in Place to Prevent Your Dreams of a Succession Story

Mixed Media

25 x 27 x 9in

2013

Fuzzy Hold on the Cycle With No Mouth to Name

Mixed Media

45 x 57 x 11in

2013