Only appearing completely vacant and abandoned, Erin Murray’s drawings and paintings actually have a lot to say, and Dirty Laundry was there to listen. The scariest part of Murray’s haunting structures is what they’re willing to divulge about the viewer – and the artist. Like her buildings, this Q&A tells all.

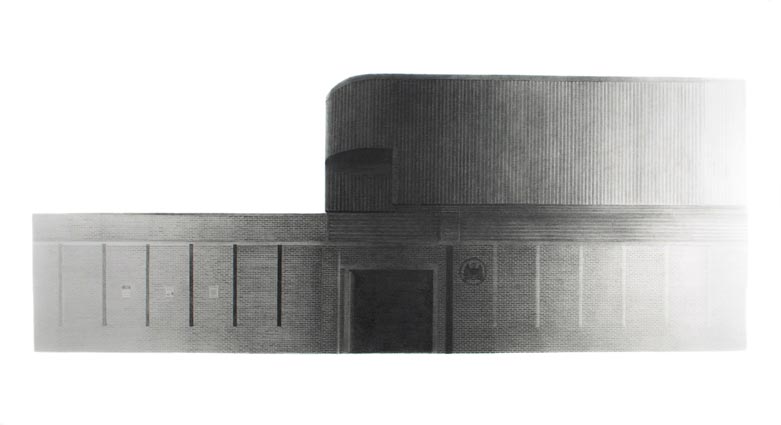

Outreach Services

22″ x 40″

Graphite on Paper

2012

To start off, your work comes from the world around you, through your eyes. Do you find most of your inspiration comes from your home of Philadelphia?

Actually, most of the subjects I use are outside of Philly, though still within its greater metropolitan area. However there’s no doubt that the experience of living here over the past 11 years has shaped my work. The city has been in a pretty dramatic state of flux during that period, and that cycle of decay and rebirth was what initially drew me to painting buildings. Now, the work is more about subtly anthropomorphizing buildings, and drawing parallels between their condition and ours. They don’t necessarily have to exist in an urban setting, and sometimes the ones I like most are so bland that they could exist anywhere. Philly is in my bones though; I almost think that some of the buildings I paint or draw are like a microcosm of Philly’s own character; they are underdogs, they have rich embedded histories, they’ve seen better days. Maybe there’s something to that.

Now, the work is more about subtly anthropomorphizing buildings, and drawing parallels between their condition and ours.

If you moved to the country, how would that affect your work?

When I was in art school I was traveling on highways a lot, and my work was inspired by the depopulated, yet manufactured landscapes that could be seen on the sides of the highway. Then I moved back to Philly and started to paint buildings. I actually started by painting an old foundation and went up from there. It’s kind of embarrassingly literal. So, if I moved to the country there’s no doubt the change of scenery would affect the work, but I bet it would still have the same underlying feelings. I think you’d have to move pretty far out to find a place that’s devoid of idiosyncratic expressions of humanity. I think access to those kinds of places has less to do with their location on the urban/rural spectrum, than with the simple issue of density: i.e., I’d probably just spend more money on gas.

Do you preserve the buildings as they are in real life, or do you change them?

Mostly preserved. Often the weirdest elements in a piece are exactly as seen – truth being stranger than fiction, so to speak. I mostly edit things out of the backgrounds if they are distracting, or forgo the background entirely. I think of my work more as portraits than landscapes, so background elements are there to play a supporting role, if at all. Lately in paintings I’ve been giving myself permission to experiment more with color, taking them further into a kind of symbolic realm.

Milesian Influence Loop, Oil on MDF Panel, 16″ x 24″, 2011

At Home in the Modern World, Oil on Plywood, 20″ x 24″, 2011

These are structures that are in every town, buildings we pass every day. Tell us about what they mean to you, and why you put so much value in them.

People are always rubbernecking as they pass by beautiful buildings. I’m no exception to that. But I find that I am excessively voyeuristic, taking in buildings of all stripes like a horny 16-year-old boy. Sometimes I have to consciously turn that part of my brain off while driving because it can be overwhelming. There’ are a couple of reasons I’ve developed into this I think. My father is a builder and untrained architect, and he built a house for our family when I was 13. It was actually quite an unusual house, circular in shape, like a cylinder with a garage extending off its side. It was very well built, but definitely had a hint of the visionary. The house was not an easy project and over the years came to symbolize much more than its parts; it was like another member of the family or, in another sense, the physical embodiment of my father’s psyche.

Years later my partner and I took on our own grueling house project, renovating a multi-unit building from shell condition. I remember when we were demo-ing and scrapping all the metal in the building all I could see as I travelled through the city was metal, everywhere. As we glazed windows I saw window glazing, everywhere. So, I think my own fraught history with buildings combined with my tendency to be intensely observant of my surroundings has made me look at buildings differently than most. It’s not about real estate or where you want to live, but about the character being projected that relates to ourselves in some way. Each building has its own set of embedded information (its history, the history of architecture, economic circumstances, etc) that we aren’t necessarily equipped to read directly, but we can perceive its presence and connect to it emotionally.

There is a definite sense of loneliness or abandonment streaming throughout your work. That, in conjunction with the subject matter of these generic buildings from American cities, some viewers might develop a correlation between your work and the current state of our country. Can you comment on that?

I would agree that the things we build tell us a wealth of information about ourselves. As an observer of buildings it’s hard not to become discouraged by the poor quality of most of what’s built nowadays. I’m not trained as an architect or historian, but it seems to me that the language of vernacular architecture has become unmoored; there’s no design standards in this postmodern world, just budgets. Development is still largely planned around our dependence on cars, which is still alienating to us even if it’s all we’ve ever known. There is sadness there but I think it’s unhealthy to dwell on it too much, or to long for the past. So, I think that’s an accurate read of the work, although I personally have more of an empathetic or accepting relationship to the buildings I paint or draw.

Choices, Choices

Oil on Plywood

12″ x 17″

2011

I find that I am excessively voyeuristic, taking in buildings of all stripes like a horny 16-year-old boy.

What is your studio practice like?

I have my studio on the first floor of my building, so I am lucky to have a short commute. I have a pretty regular schedule each day that nets me between 30 to 40 hours a week. I vacillate between painting and drawing, working in short series. One usually gives me a break for the other. With few exceptions at the beginning or end of a painting, it’s one piece at a time. My studio is small, but has a 6-foot-long drawing table for graphite work, and a messier area in the corner for painting.

Public Private

12″ x 17″

Oil on Panel

2011

Walk us through your process.

Well, the paintings are done on plywood panel. I prime the panel with gesso, usually troweling it on with a taping knife and then sanding it when dry to get a very smooth surface, but not getting too hung up on the perfection of it; you’ll see the occasional taping knife mark or buildup around the edges. The panel is mounted on some sort of cradle or hanging mechanism – I’m always experimenting. I start with thumbnail sketches based on photo references and then scale up the composition to the panel in pencil. The first layer of the painting is basically coloring – I fill in everything roughly and it’s a chance to experiment with colors and make mistakes. The second and often third layer is me revisiting each area more carefully, repeat until mostly satisfied. For the last layers I break out the glazing medium to add washes of color, which adds intensity to the colors and can also sharpen things. I use watercolor brushes throughout, which have to be replaced often but are great for detail work and for smoothing gradients. An average-size painting will take about two weeks, something like 50 hours over the course of 15 sittings.

The drawings are more straightforward. Lots of careful measuring. I use tortillion stumps and the graphite pencils themselves to blend. Often I’ll use both graphite and charcoal to get a greater range of values. They resist each other, so that usually involves careful blending at their border. One thing I actually appreciate about the drawings is that they’re more rote; you can have whole days of just filling in bricks. Some days, that’s a nice break. I’d say the drawings take slightly less time than the paintings, unless there’s lots of bricks.

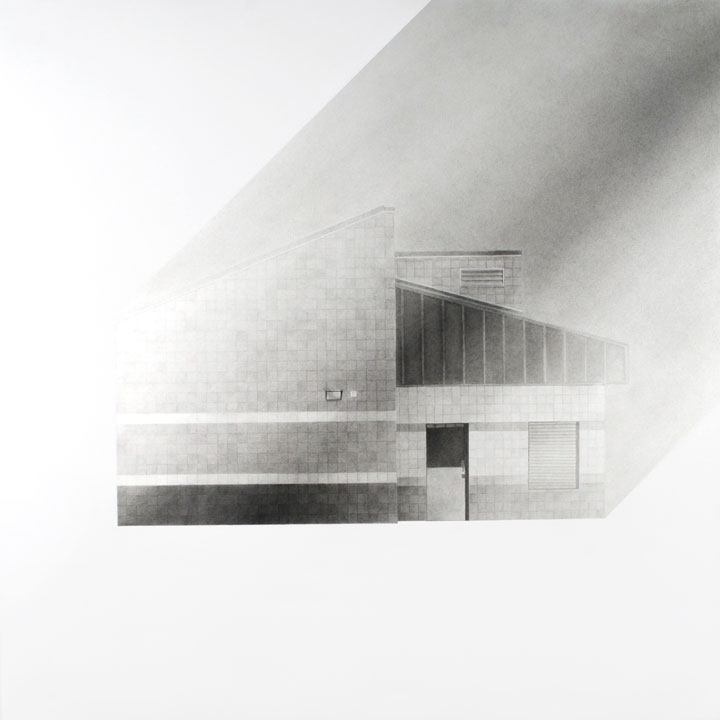

Present

Graphite on Paper

36″ x 36″

2012

Future

Graphite on Paper

36″ x 36″

2012

On top of the amount of detail in your work, you experiment a lot with light. Some pieces introduce large shapes of ghostly gradients. These elements are bold and give the structures something else to interact with. What is the relationship of these lights and shapes to you and/or your work? What do they mean?

For me the gradients and beams of light are a way to take the structure further into a symbolic or psychological realm. There’s no need for me to tether my subject to reality by including accurate background information, atmospherics, or typical figure-ground relationships. It’s a way to hint to the viewer that they are meant not to see it as a traditional landscape but more as a contemplative space. In a recent series of drawings, I used the gradients in a more conceptual way, using strong diagonals to indicate directional time, as a way to show how buildings can project information about themselves through the spectrum of time, i.e a building always tells us something about its past and present, and also can project an idea of the future.

What caused you to put down the paintbrush and focus more on drawing with graphite? And how do you think the absence of color has changed your work?

I did a lot of drawing in art school. Painting was more of a challenge so once I started down that road I didn’t stop until I felt I had a handle on it. Then I felt a little stifled, like I had hit a wall, so I decided it couldn’t hurt to change courses. I had really fond memories of working with charcoal; I’ve always loved its velvety texture. So, I bought a drawing table, since my studio had never been set up to accommodate drawing, which is no small barrier right there. Anyway, I’m glad I returned to it because it freed me up immediately, in ways that I could bring back to the paintings as well. My learning process is really visible if you look at my work over time. It’s always been like baby steps. I still don’t know if that’s embarrassing or essential.

My learning process is really visible if you look at my work over time. It’s always been like baby steps. I still don’t know if that’s embarrassing or essential.

The absence of color that came from switching mediums definitely added a haunting quality to the work, and enhanced the stillness. Like a black-and-white film, the buildings are taken out of their original time and place and sort of exist in their own dimension, which has always been my goal. In the studio now I am working on new paintings that hopefully retain that quality but with vibrant color.

These buildings bring up such a sense of the uncanny. So familiar, yet unfamiliar and strange. The images feel like they have been wiped clean of all human life, leaving just subtle traces- an open blind, a reflection, a tag of graffiti- just a hint of history. The ambiguity forces the viewer to input themselves and their personal experiences into the pieces, and everyone walks away with a different take on the work. What is your own personal interpretation?

I want them to be like empty vessels to be filled with whatever the viewer brings to them. We all have our strong associations with buildings that allow us to craft our own narrative if we want to. I personally see them as mirror reflections of ourselves. As Mies Van der Rohe said, “Architecture is the will of an epoch translated into space.” So I look at buildings and think about how they reflect our culture but also how they reflect enduring individual human characteristics too; things like absurdity, humor, obstinence, resilience, utopian thinking, and failure.

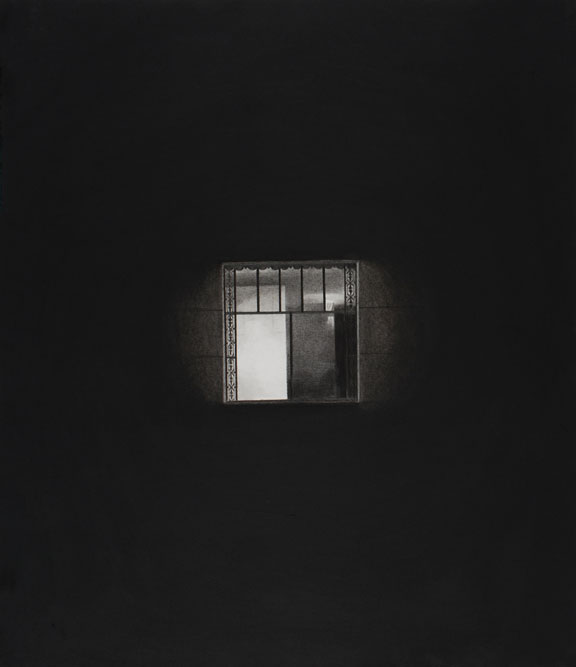

Untitled Abstraction (Frankford)

Graphite and Charcoal on Paper

15″ x 13″

2012

Untitled Abstraction (Walnut)

Graphite and Charcoal on Paper

15″ x 13″

2012

So I look at buildings and think about how they reflect our culture but also how they reflect enduring individual human characteristics too; things like absurdity, humor, obstinence, resilience, utopian thinking, and failure.

Have you received any comments or reviews about your work that took you completely by surprise? If so, how did that affect you?

I did have one review where the author didn’t quite get how drawings of very mundane 50s-era municipal buildings could be emblematic of a “faded romanticism,” or why I would strive to monumentalize a type of failed architecture. She said, “Is she aware architecture had reached a low ebb at this time?” as if I just hadn’t picked good enough buildings to celebrate. It was discouraging that she completely missed the point, but you can’t win ’em all, and probably shouldn’t want to.

What other artists inspire you?

De Chirico, Peter Doig, Wendy White, Neo Rauch, Zoe Strauss, Bernd and Hilla Becher, April Gornik, Jennifer Bartlett, Ed Ruscha, Lebbeus Woods

Who would you never work for, no matter how much they offered to pay?

Toll Brothers.

If your face was on the front of a restaurant, what would be served inside?

Fruit roll-ups and toast.

Would you rather live in outer space or underwater?

I think outer space would feel less claustrophobic. Bonus points for lack of gravity.

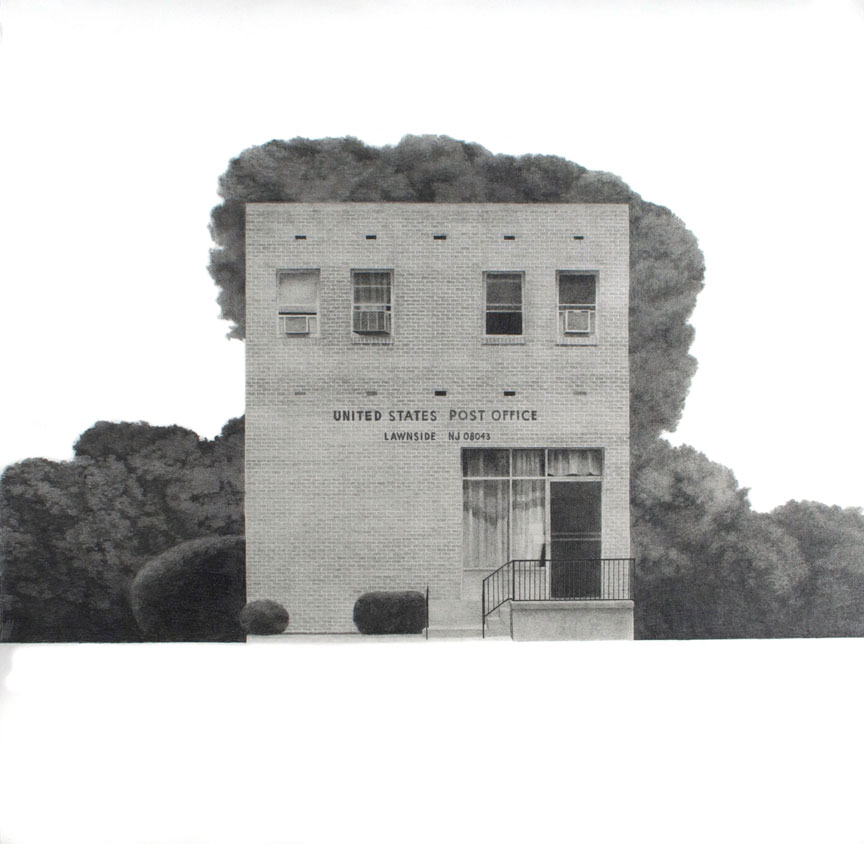

PO Box

Graphite on Paper

22″ x 22″

2012