Least of all of the things I expected upon moving to London was that life in the city would function as an abject lesson in humility and aloneness. Not to mention that those two things would be so beneficial to a practice that had, until that point, been predicated on over-confidence and relationships.

See, for me, I’d come from a city where the social life and broadcast goals of the artist are paramount, and where the ability to live for what you want is something that can be accomplished and is encouraged. London isn’t like that – the only way I can think to describe it is: In London, everyone has a destination all the time, and so everyone is constantly moving, and everything is in flux. It’s so big, and everybody here is out to prove themselves, or to live a comfortable life, or to do what they can to get by. And because of that, it’s very easy to get lost.

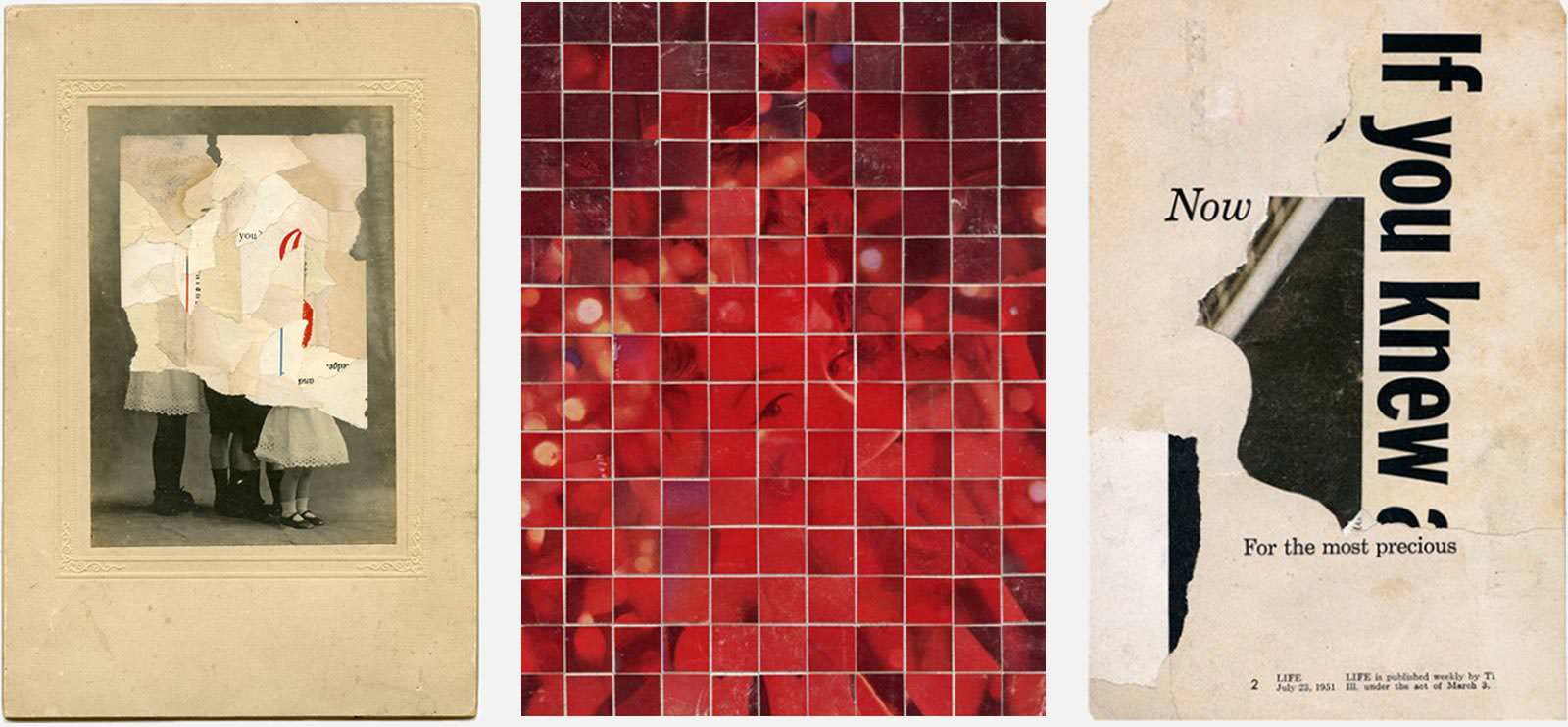

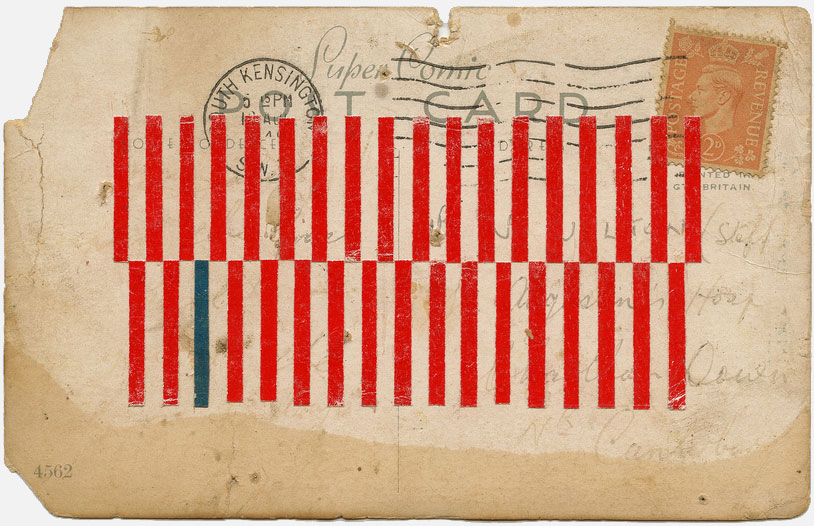

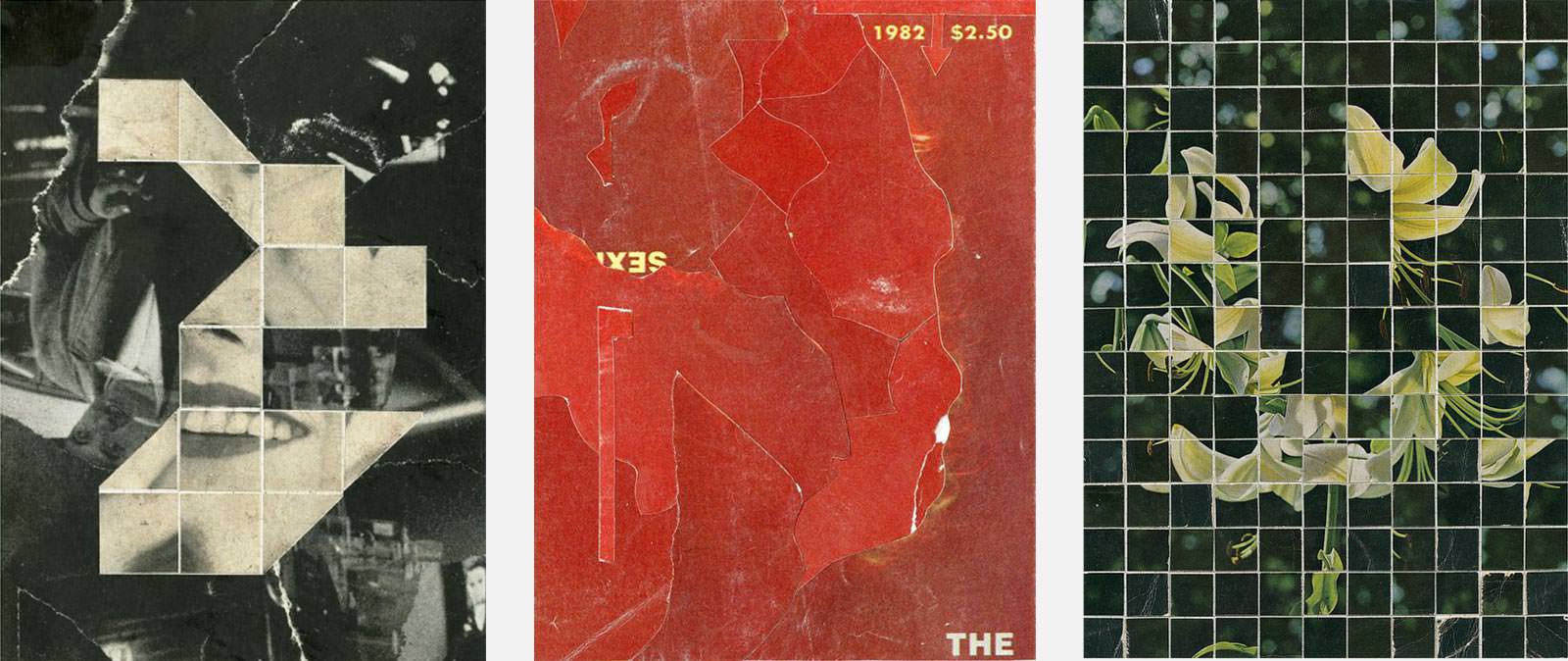

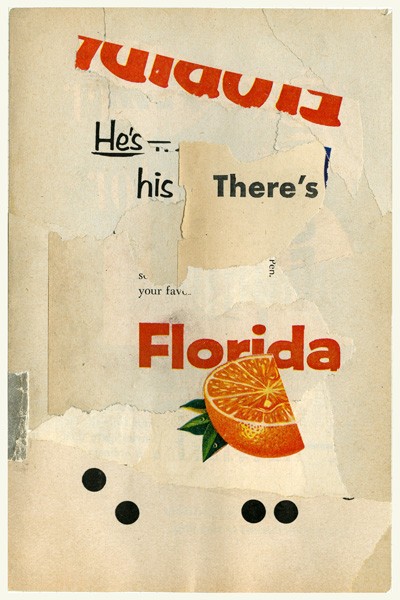

In Toronto nothing changes, and so something as strange as building a portrait practice concurrent to building a social life is relatively normal. Or if not normal, then looked upon happily rather than…ignored. This absolutely killed me when I moved. But even worse, it killed the practice that I’d hoped to establish myself with upon arrival. For six months I didn’t photograph a single person, my camera gathered dust, and collage became a refuge for an increasingly unbearable living situation. Everything was broken.

That said, I don’t want to make myself sound like a victim – my hardheaded desire to retreat into art was as aggressive and unfriendly as I perceived others around me to be – but it did change me. It changed the way I engaged with my work, with people, and with myself. Gone was the complete happiness in simply doing. Living somewhere so big had brought about a need to be noticed, to feel like what I was doing somehow impacted the world. And it also brought in the bordering-on-lunacy feel of living in a vacuum: that everything I did reached absolutely no one, that success (and by extension, a life in art) was a mirage, and that the only way to break out of the silence was by doing, doing, doing.

What this resulted in was a completely different, colder person. Someone who I’m happy to be, but someone who didn’t exist before I moved. A man plagued by self-doubt and frustration, with the only cure being “do more work and do it better,” constantly striving to reach some perfect end while also producing a steady stream of collages, photographs, portraits, drawings, pieces of writing, typographic studies, and designs. I ride my bike from Stamford Hill to Shoreditch in the morning and the only thought is: “How do I make myself better?” The work, and the continued success of it, is constantly on my mind, and on the back-end of the thought is the thought that at any moment it could all collapse. That what success I’ve managed here is built on a shaky foundation, and that I must keep it up, or the whole thing will crumble.

The work, and the continued success of it, is constantly on my mind, and on the back-end of the thought is the thought that at any moment it could all collapse.

I don’t think these are especially dark feelings though, and I always wonder: Was I just exceptionally lucky to have the friends I did, the community I did, in Toronto? Have I forgotten those first few years there, and is the emptiness of a place always present upon arrival? Is it just time and knowledge that grounds you? I honestly don’t know. All I know is that in the last year and a half since I moved, I’ve produced more work than I ever have before, including long-term landscape photography projects (The Seaside Town Index and American Homes), my most mature bodies of collage work (Histories and There Must Be More to Life Than This) and, gratefully, a return to photographing people, something that I love and didn’t know how much I missed until I began doing it again regularly. I love living in London. I love the pace, and I love the fear of lagging behind that the pace brings out.

I miss Toronto; I’ll never know a place so good or a group of friends so kind, and I think about them, literally, every single day. But I know I can’t go back. And that’s a very, very, very, very strange thought.